Injuries We Treat in Pasadena, TX

Expert Treatment for Car Accident & Personal Injury Victims

At AccidentDoc Pasadena, we specialize in comprehensive medical care for accident-related injuries. Our board-certified physicians and injury specialists provide evidence-based treatment for whiplash, back injuries, soft tissue damage, and more. With over 400+ patients successfully treated, we understand the physical, emotional, and legal complexities of accident recovery. We accept all insurance, including PIP and MedPay, and offer Letter of Protection treatment—meaning $0 out-of-pocket until your case settles. Same-day appointments available for new patients.

Whiplash & Neck Injuries

Whiplash is the most common injury resulting from car accidents, affecting over 3 million Americans annually. This cervical spine injury occurs when sudden deceleration causes the head to rapidly move forward and backward, straining the delicate muscles, ligaments, and vertebrae in the neck. At AccidentDoc Pasadena, our board-certified physicians specialize in comprehensive whiplash treatment, from initial diagnosis through complete recovery.

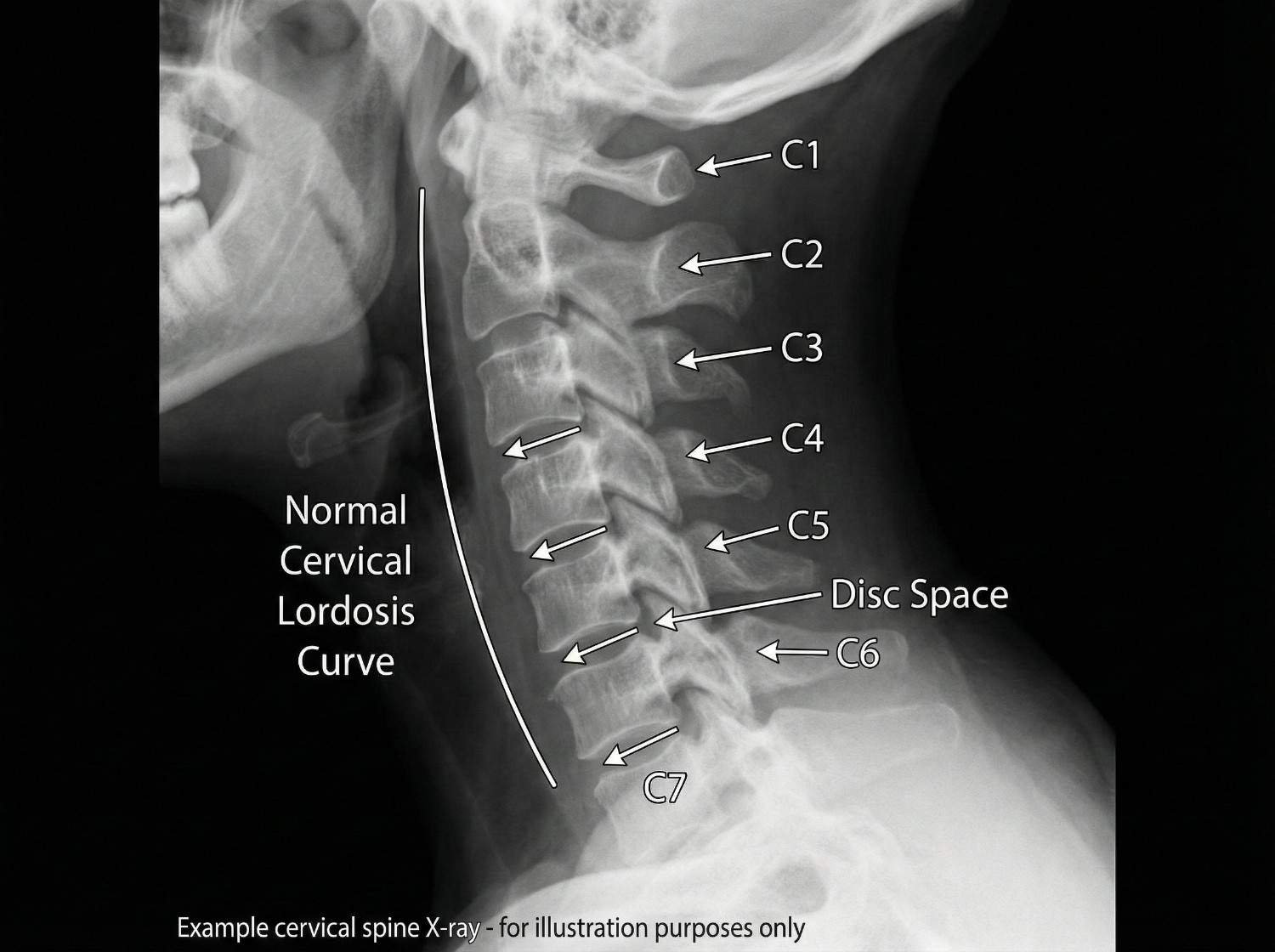

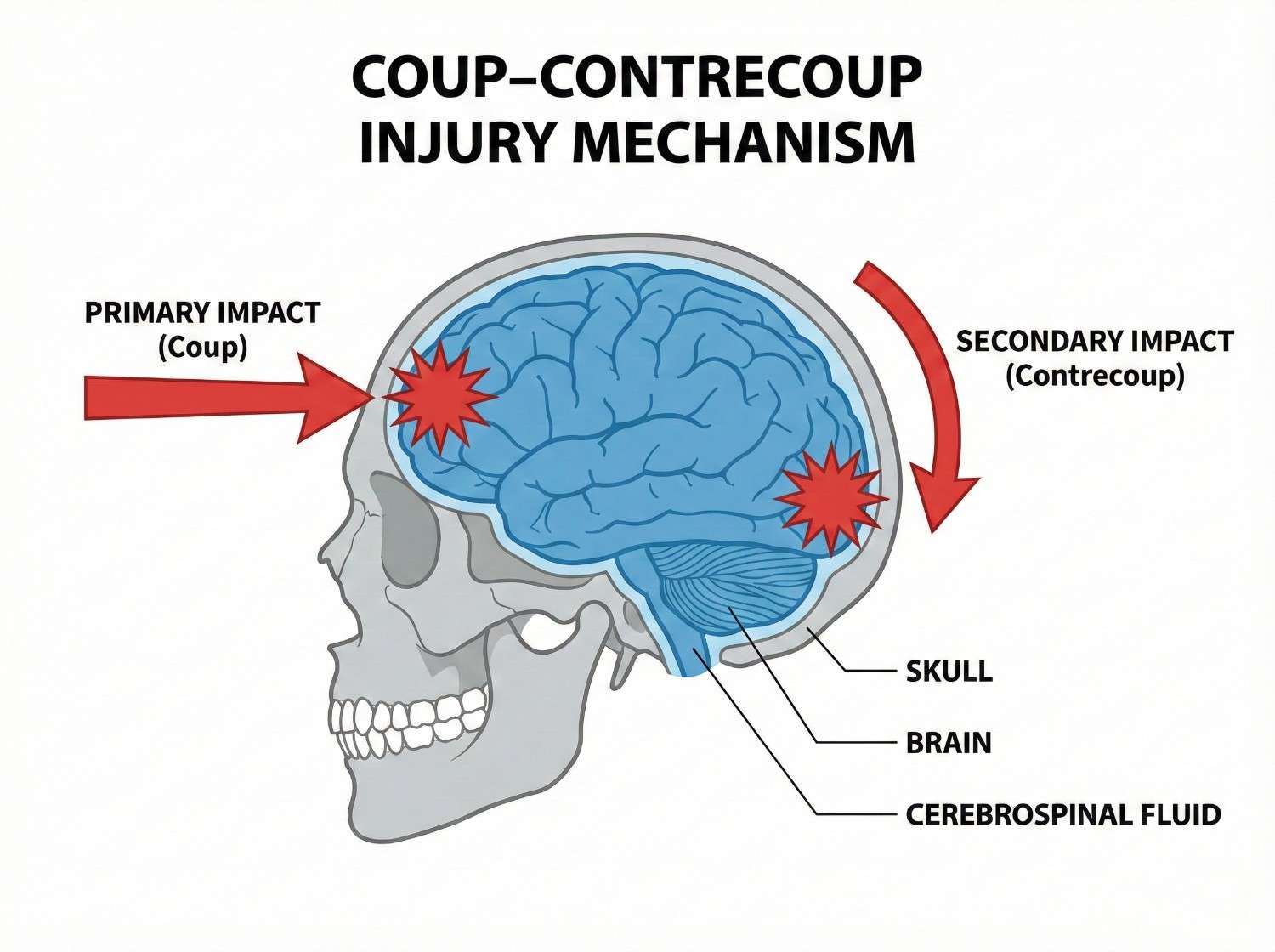

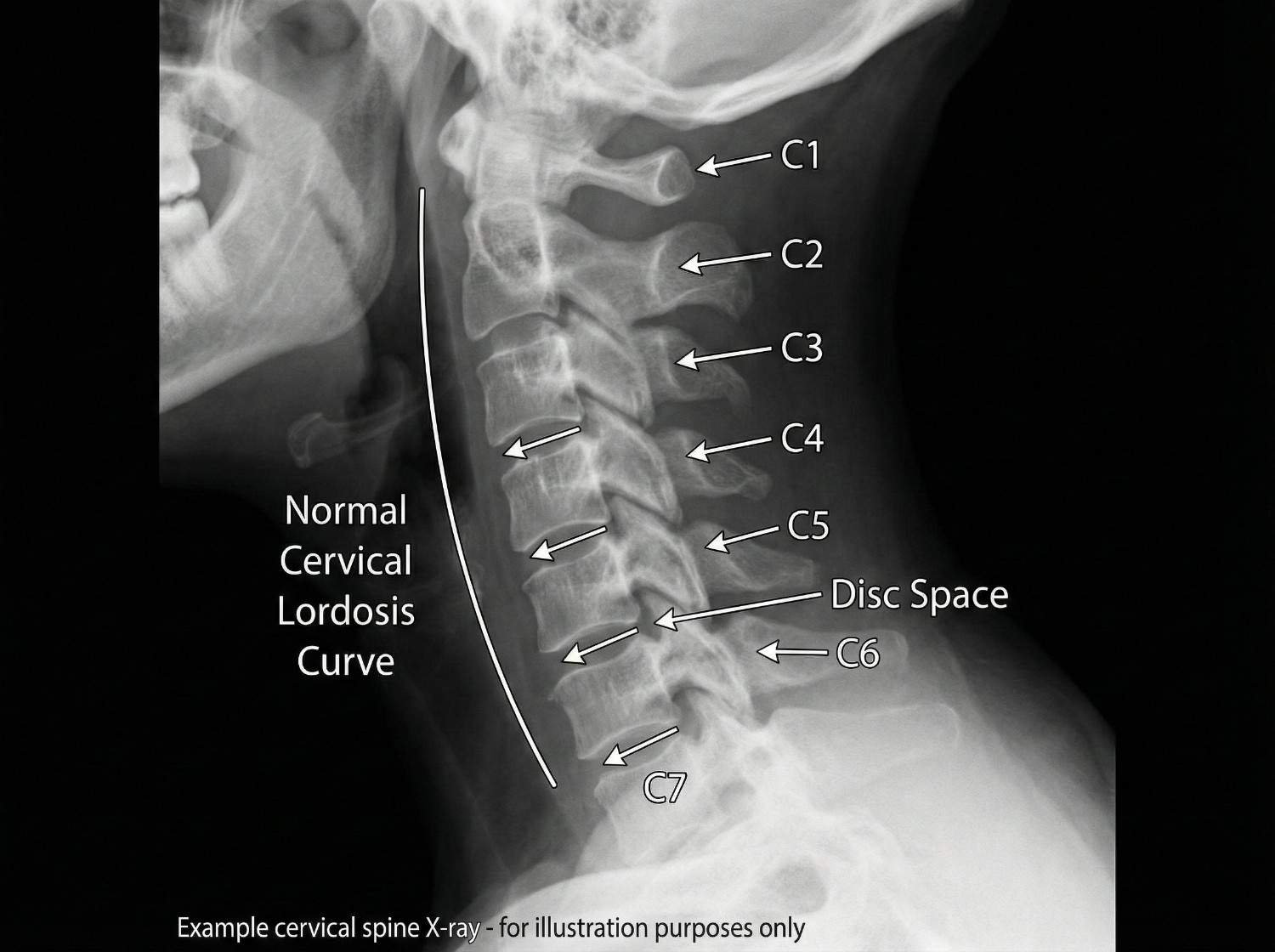

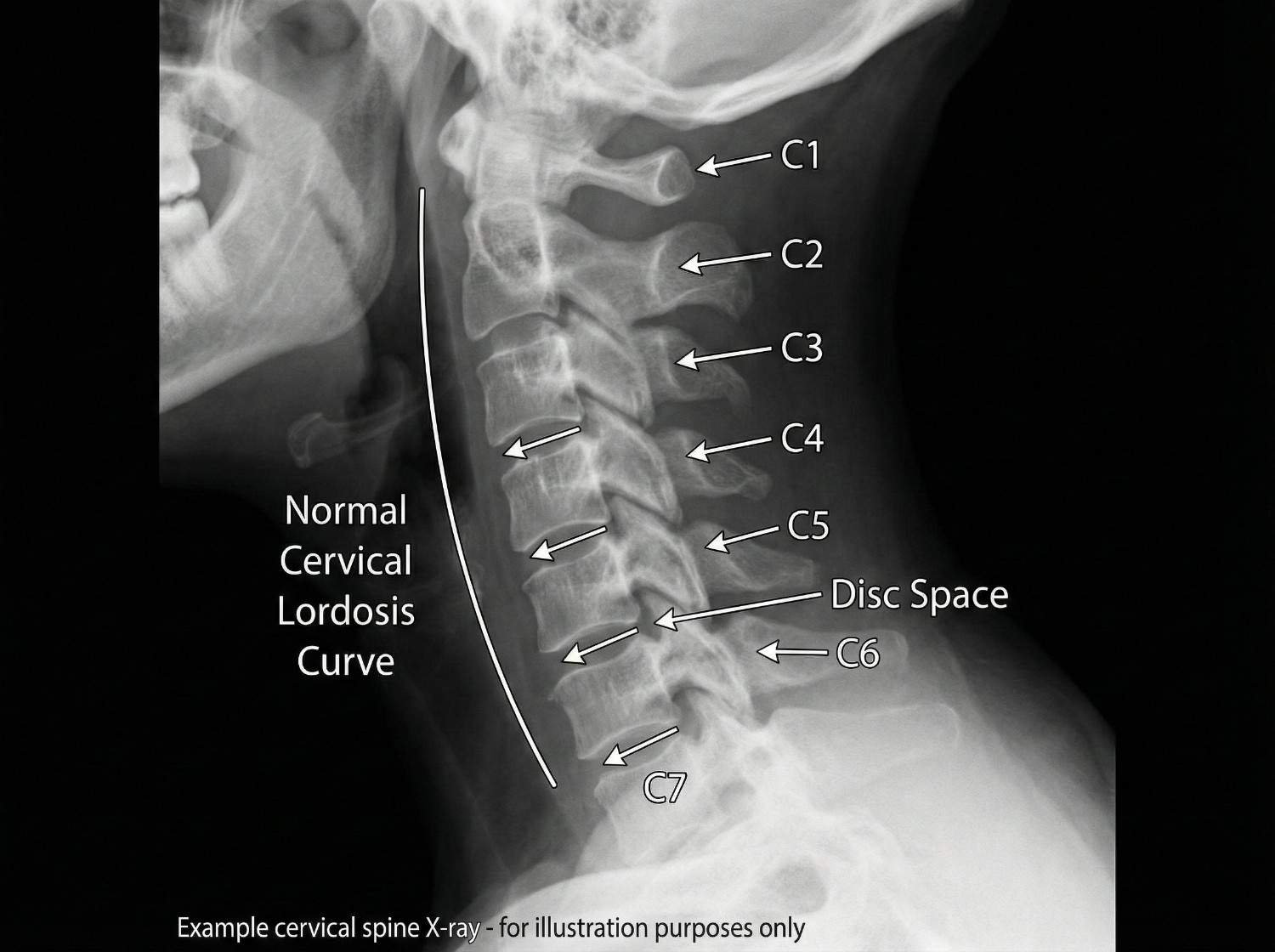

Whiplash is a complex soft tissue injury involving the cervical spine's intricate network of seven vertebrae (C1-C7), intervertebral discs, facet joints, muscles, ligaments, and nerve roots. The injury mechanism typically involves a hyperextension-hyperflexion sequence: during rear-end collisions, the torso is thrust forward by the seatback while the head momentarily remains stationary due to inertia. This creates an S-shaped curve in the cervical spine, straining the anterior longitudinal ligament and anterior neck muscles. Milliseconds later, the head snaps forward into hyperflexion, overstretching the posterior ligaments, facet joint capsules, and paraspinal muscles.

The forces involved can exceed 5G of acceleration, causing microscopic tears in muscle fibers, ligament strains, facet joint capsule injuries, and in severe cases, intervertebral disc damage or nerve root compression. The C5-C6 and C6-C7 spinal segments bear the greatest stress due to their location at the cervical spine's mobile center. Research published in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy demonstrates that even low-speed collisions (5-10 mph) can generate sufficient force to cause whiplash, as the sudden acceleration-deceleration exceeds the neck's protective muscle contraction response time.

What makes whiplash particularly challenging is its biomechanical complexity. Unlike a simple muscle strain, whiplash often involves multiple tissue types simultaneously: muscle-tendon units, ligamentous structures, facet joint capsules, and sometimes disc integrity. The injury cascade doesn't stop at the moment of impact—inflammatory mediators released by damaged tissues can sensitize nerve endings, leading to chronic pain if left untreated. Our team at AccidentDoc Pasadena employs advanced diagnostic protocols to identify all involved structures, ensuring comprehensive treatment rather than symptomatic relief alone.

Rear-end collisions account for approximately 80% of all whiplash injuries, making them the leading cause by a substantial margin. These accidents generate the classic hyperextension-hyperflexion mechanism as the struck vehicle rapidly accelerates forward while the occupant's head lags behind. Even at seemingly minor speeds of 5-15 mph, the force differential between vehicle acceleration and head inertia creates significant cervical strain. Side-impact collisions represent the second most common cause, producing lateral whiplash where the head is thrown sideways, straining the scalene muscles and contralateral facet joints.

Frontal collisions, while often associated with more severe injuries, also cause whiplash through a hyperflexion-hyperextension sequence—the reverse of rear-end impacts. Here, the head initially snaps forward (hyperflexion) before rebounding backward (hyperextension). Pedestrian-vehicle collisions generate particularly severe whiplash as the unrestrained pedestrian experiences full-body acceleration without seatbelt protection, often resulting in rotational head movements that combine flexion, extension, and lateral forces simultaneously.

Less common but significant causes include slip-and-fall accidents where the head snaps backward upon impact, sports injuries involving helmet-to-helmet contact or sudden deceleration (football, hockey, rugby), and workplace accidents such as being struck by falling objects or equipment. Even aggressive amusement park rides with rapid acceleration-deceleration cycles have been documented as whiplash causes. The common denominator across all mechanisms is sudden, forceful neck movement that exceeds the cervical spine's physiological range of motion before protective muscle reflexes can activate.

In Pasadena and the greater Houston area, 18-wheeler accidents on Highway 225 and I-45 produce particularly severe whiplash injuries due to the massive size differential between commercial trucks and passenger vehicles. The forces generated in these collisions often result in Grade 2 or Grade 3 whiplash (moderate to severe) with associated complications like disc herniations or radiculopathy.

- Rear-end collisions (80% of cases) - classic hyperextension-hyperflexion

- Side-impact accidents - lateral whiplash with scalene muscle strain

- Frontal collisions - reverse mechanism with airbag forces

- Pedestrian accidents - rotational forces without restraint

- Slip-and-fall with head snap - hyperextension dominant

- 18-wheeler accidents - high-force impacts with severe tissue damage

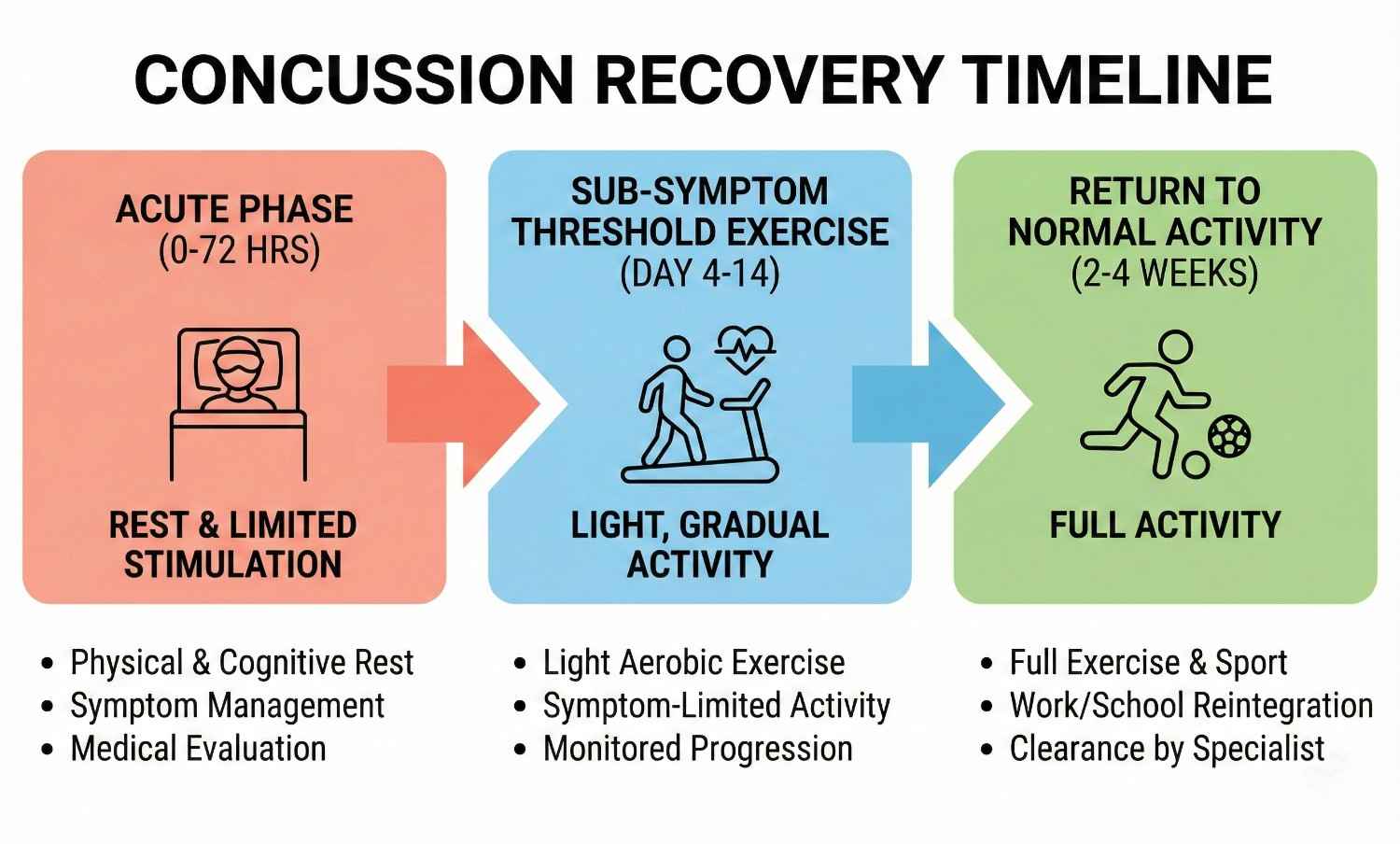

Whiplash symptoms follow a characteristic temporal pattern that clinicians use to assess injury severity and predict outcomes. Immediate symptoms (0-6 hours post-injury) include neck stiffness, reduced cervical range of motion particularly in rotation and extension, muscle spasms palpable in the paraspinal muscles, and localized pain at the injury site. These acute symptoms reflect the initial inflammatory response and protective muscle guarding. Many patients report feeling "fine" immediately after the accident, only to develop severe symptoms hours later as inflammatory mediators accumulate and muscle spasms intensify.

Delayed symptoms (24-72 hours post-injury) are hallmark features of whiplash and include cervicogenic headaches originating from the occipital region and radiating forward, upper back pain between the shoulder blades (thoracic paraspinal muscle involvement), shoulder pain from muscle strain and referral patterns, dizziness or vertigo from cervical proprioceptor dysfunction, TMJ pain from jaw clenching during impact, and cognitive difficulties like concentration problems or mental fog. This delayed onset occurs because tissue inflammation peaks 24-48 hours after injury, and microscopic muscle tears don't produce pain until inflammatory swelling develops.

Chronic symptoms (persisting beyond 3 months) develop in approximately 50% of whiplash patients without proper treatment and indicate transition to chronic whiplash-associated disorder (WAD). These include persistent neck pain with activity-related flares, radicular symptoms like arm numbness, tingling, or weakness indicating nerve root compression from disc herniation or foraminal stenosis, chronic headaches often refractory to over-the-counter medications, reduced cervical mobility with measurable range of motion deficits, sleep disturbances from pain-related arousals, and psychological symptoms including anxiety about driving or chronic pain-related depression.

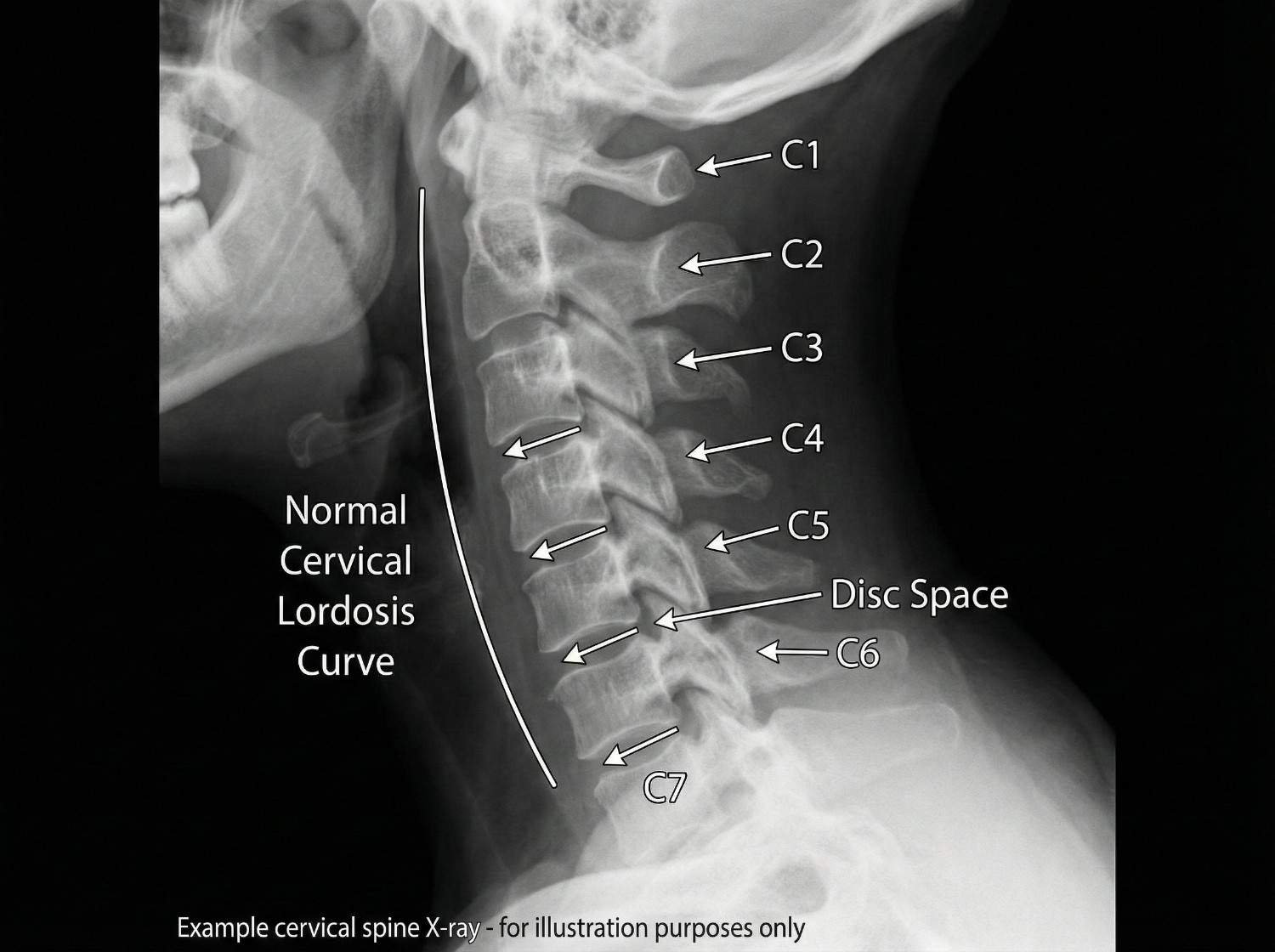

The Quebec Task Force Classification System grades whiplash severity from I (neck pain without objective findings) to IV (neck pain with fracture or dislocation). Grade II injuries (neck pain with musculoskeletal signs) represent the majority of cases we treat at AccidentDoc Pasadena. Early intervention within the first 72 hours significantly improves outcomes, which is why we offer same-day appointments for accident victims.

| Symptom | Timing / Description |

|---|---|

| Neck stiffness and pain | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Reduced range of motion | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Cervicogenic headaches | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| Shoulder/upper back pain | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| Arm numbness/weakness | Delayed or Chronic |

| Dizziness or vertigo | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| TMJ pain | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| Cognitive difficulties | Delayed or Chronic |

| Chronic pain with flares | Chronic (>3 months) |

| Sleep disturbances | Chronic (>3 months) |

Accurate whiplash diagnosis requires a systematic approach combining clinical examination with appropriate imaging studies. Our evaluation begins with a detailed medical history documenting accident mechanism, time to symptom onset, symptom progression, and any neurological symptoms. This information guides the physical examination and imaging selection.

Physical examination assesses multiple cervical spine parameters: active and passive range of motion measurement in six planes (flexion, extension, right/left rotation, right/left lateral flexion) using inclinometry or goniometry for objective documentation. We palpate all cervical vertebrae (C1-C7) for point tenderness, assess paraspinal muscle tone and spasm severity, and examine facet joint tenderness with pressure over the lateral masses. Neurological testing includes deep tendon reflexes (biceps C5, brachioradialis C6, triceps C7), sensory examination in all dermatomes, and manual muscle testing for myotomal weakness. Spurling's test (cervical compression with rotation and extension) reproduces radicular symptoms if nerve root compression exists.

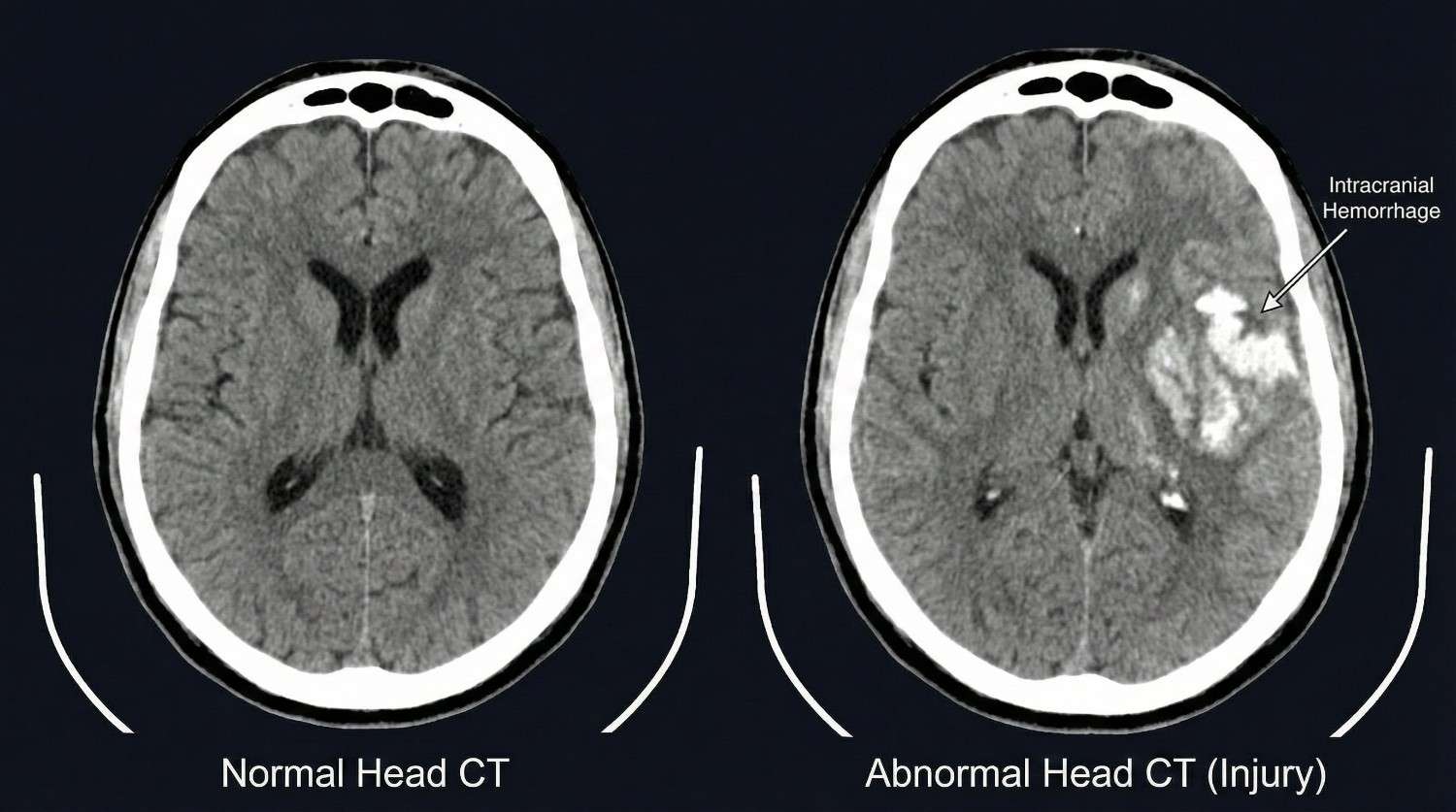

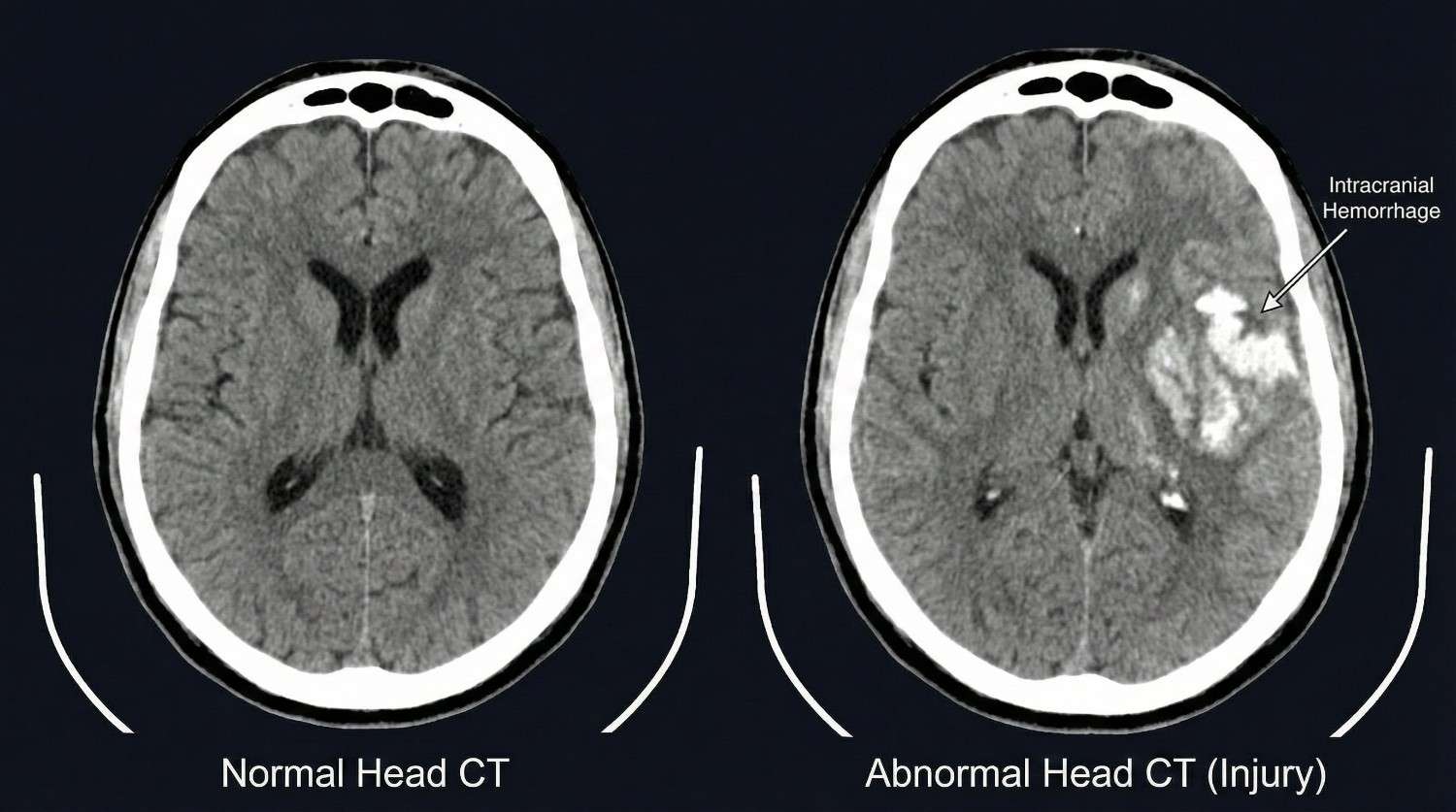

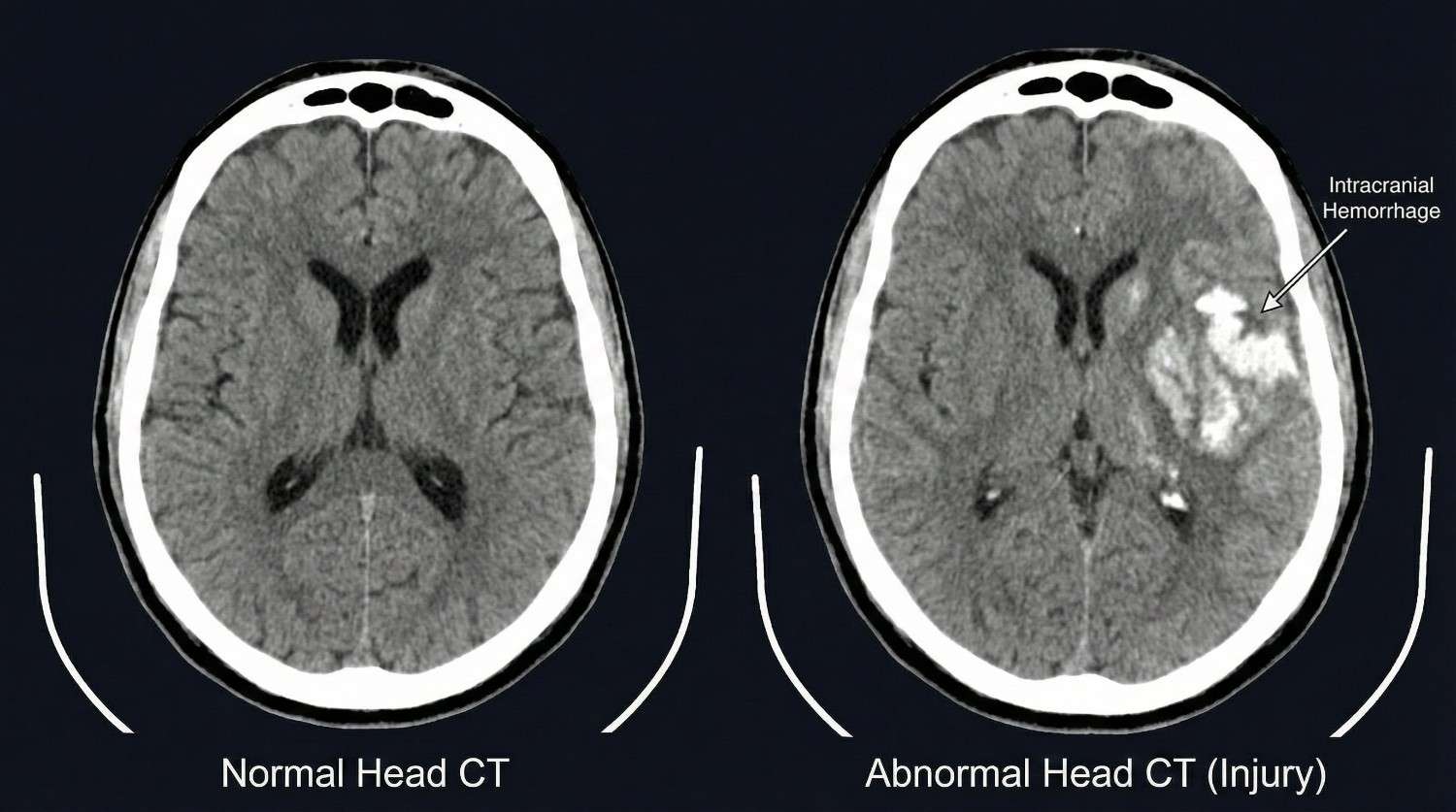

Imaging studies are selected based on clinical presentation: Standard cervical X-rays (AP, lateral, open-mouth odontoid) are initial studies to rule out fractures, assess vertebral alignment, measure cervical lordosis, and evaluate disc space heights. While X-rays don't visualize soft tissues, they identify bony abnormalities and instability. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is the gold standard for soft tissue evaluation, revealing disc herniations, ligament tears (especially the alar and transverse ligaments at C1-C2), facet joint effusions indicating capsule injury, spinal cord signal changes, and nerve root compression. We order MRI when neurological symptoms exist, severe pain persists beyond 4-6 weeks, or clinical examination suggests disc or ligament injury.

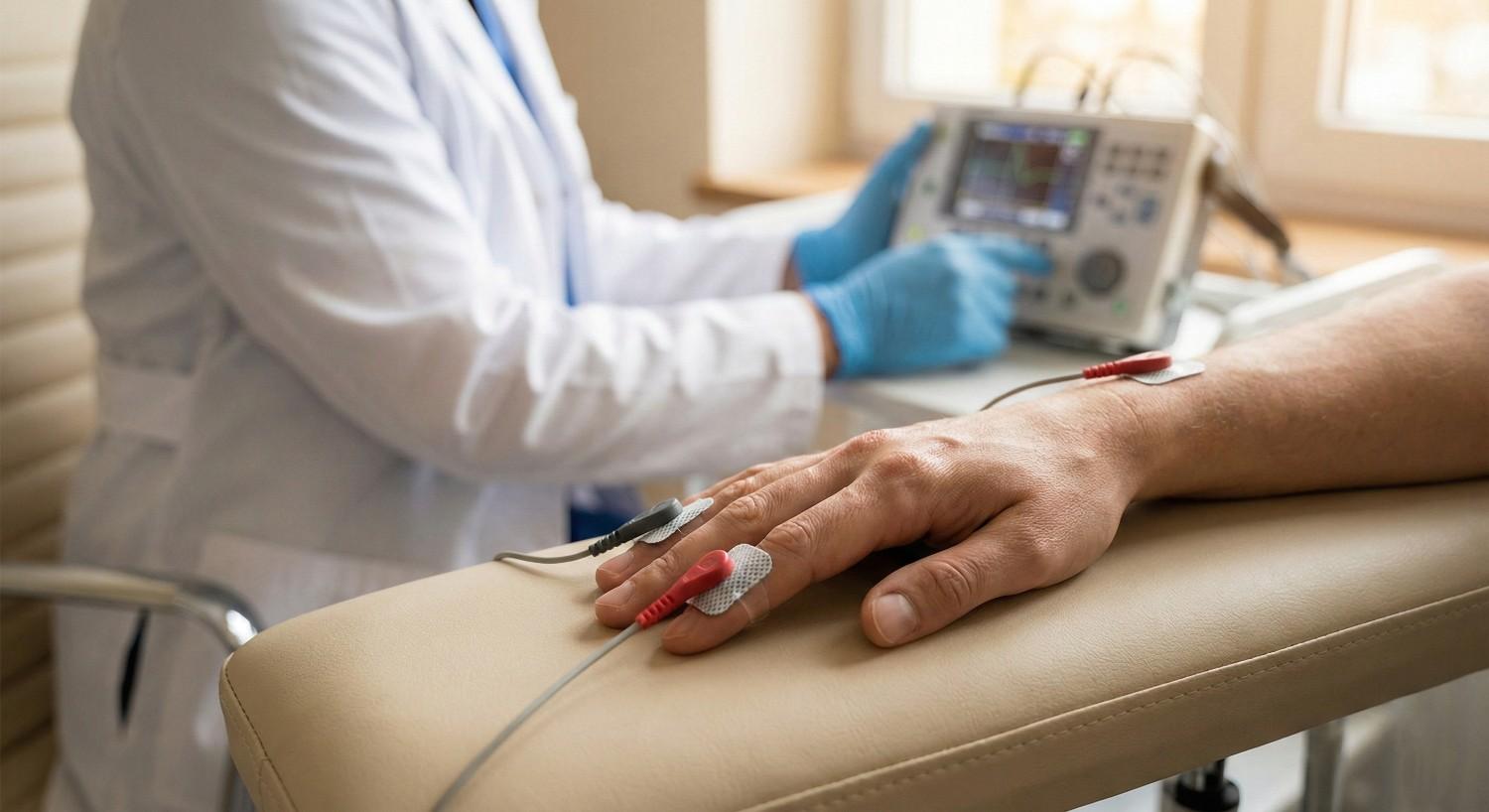

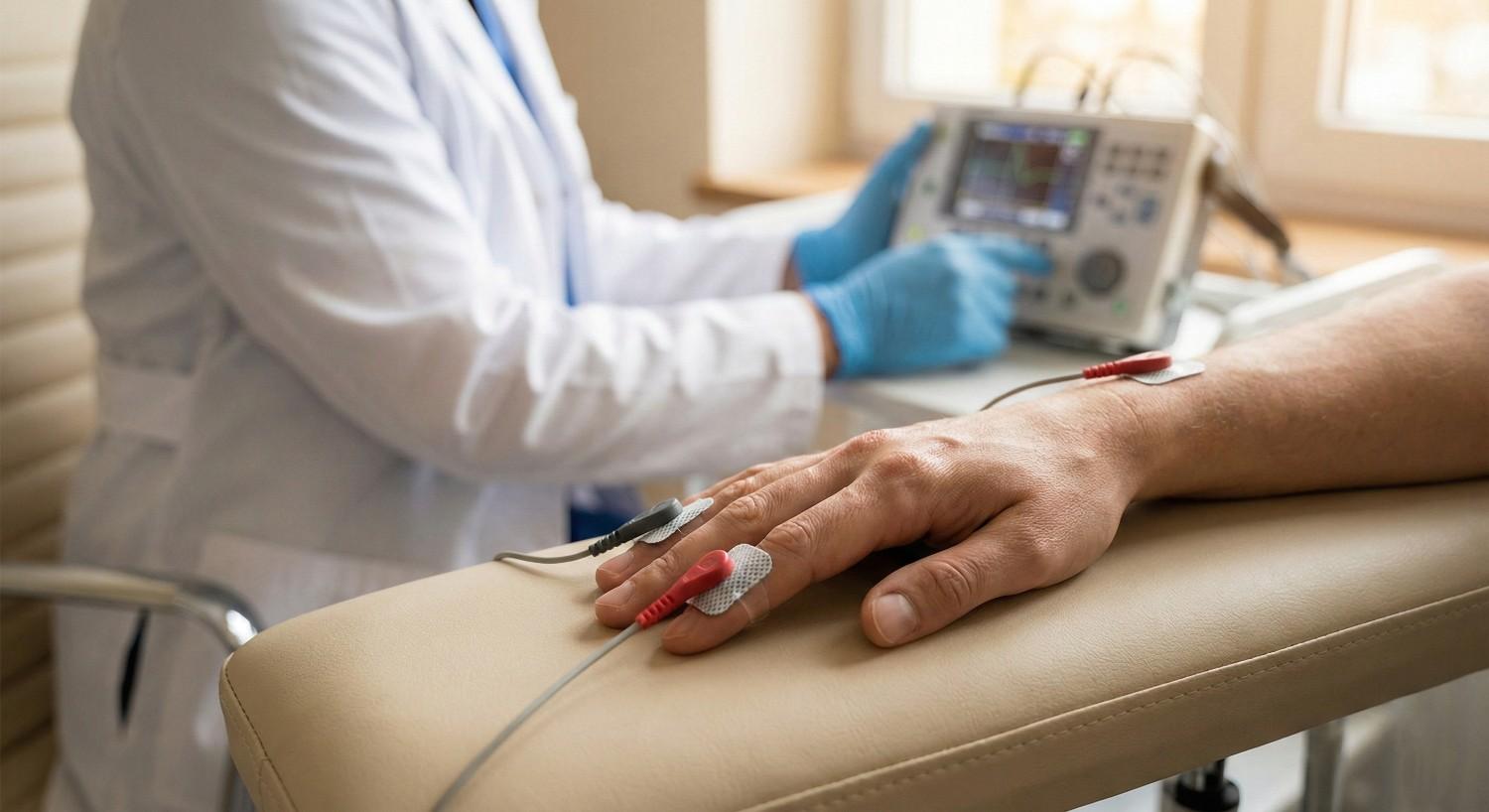

CT scanning provides superior bony detail and is reserved for suspected fractures not visible on X-ray, especially C1-C2 injuries or facet fractures. Electrodiagnostic studies (EMG/NCS - electromyography/nerve conduction studies) performed 3-4 weeks post-injury can confirm radiculopathy when MRI findings are equivocal, differentiating nerve root injury from peripheral nerve entrapment.

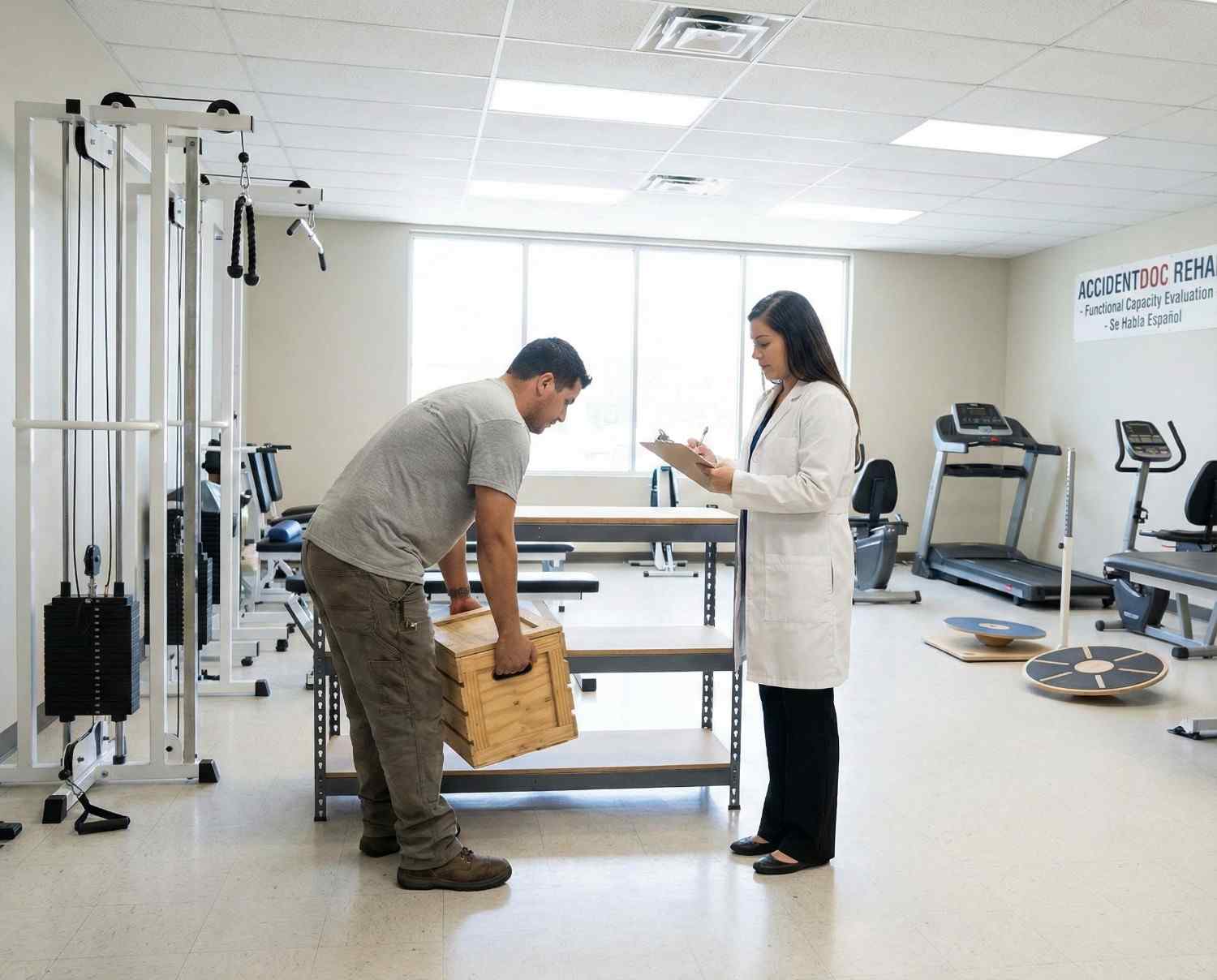

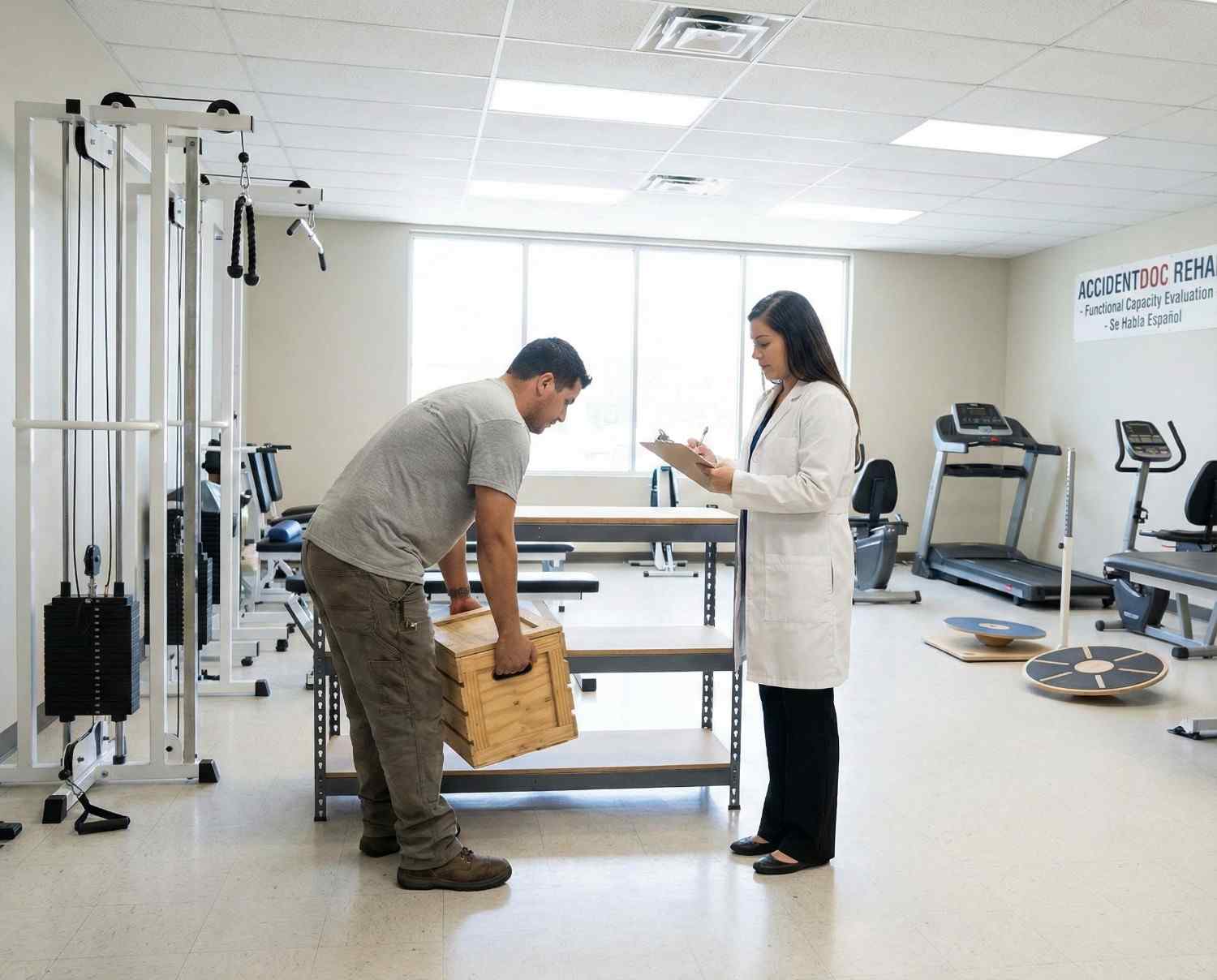

Functional capacity evaluations objectively measure how whiplash affects daily activities, providing documentation for personal injury claims and return-to-work decisions. This comprehensive diagnostic approach ensures we identify all injury components, enabling targeted treatment rather than generic neck pain management.

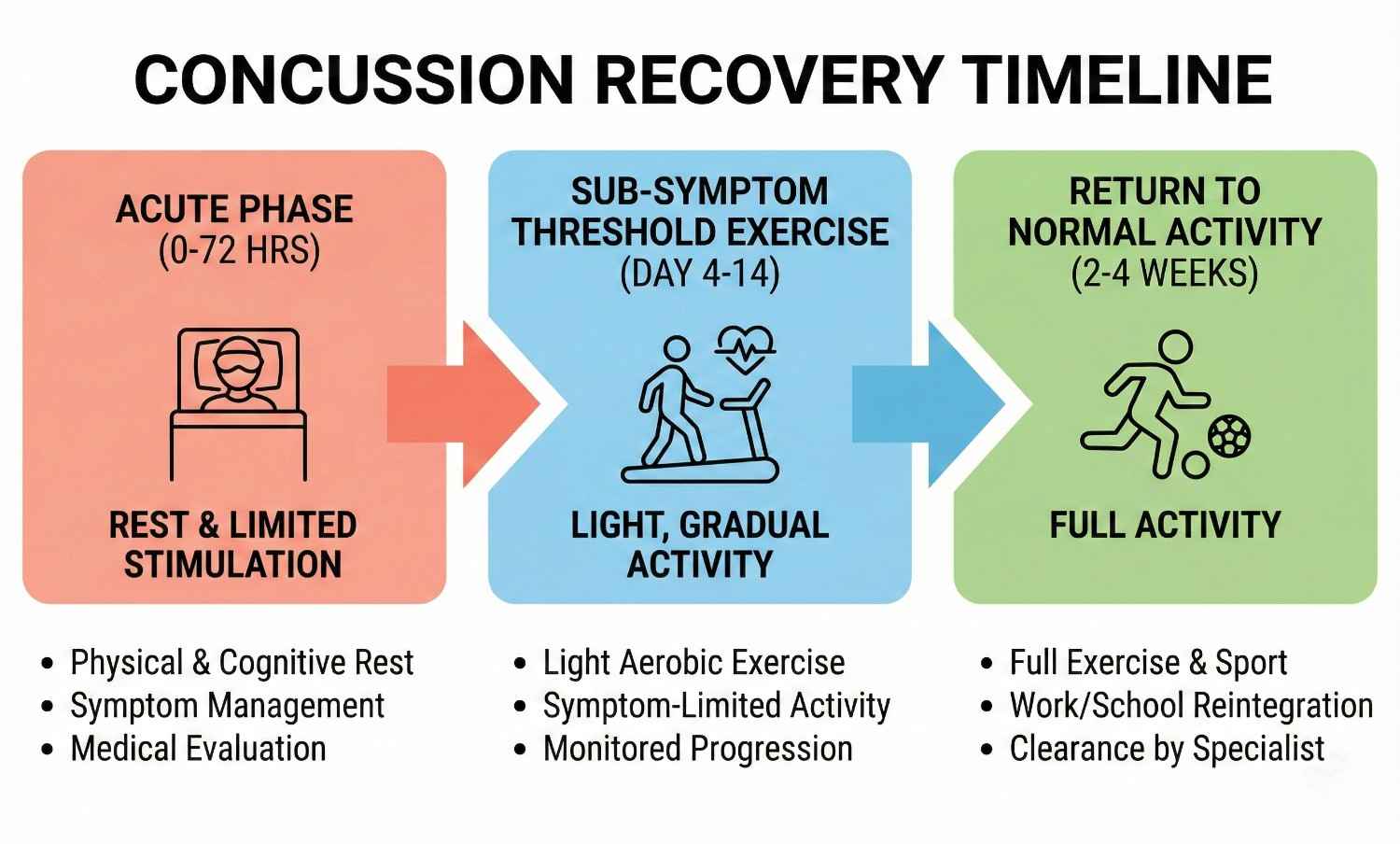

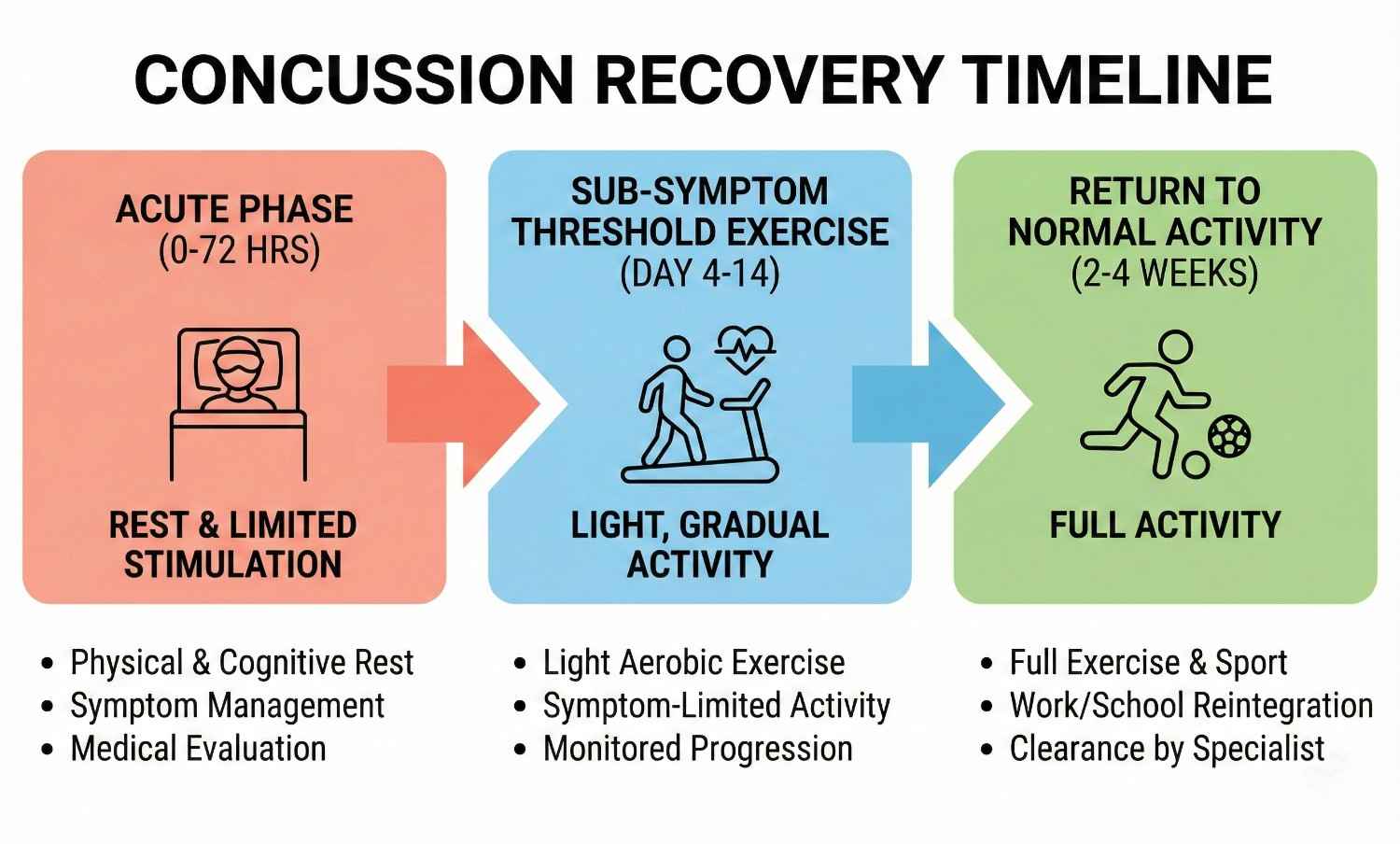

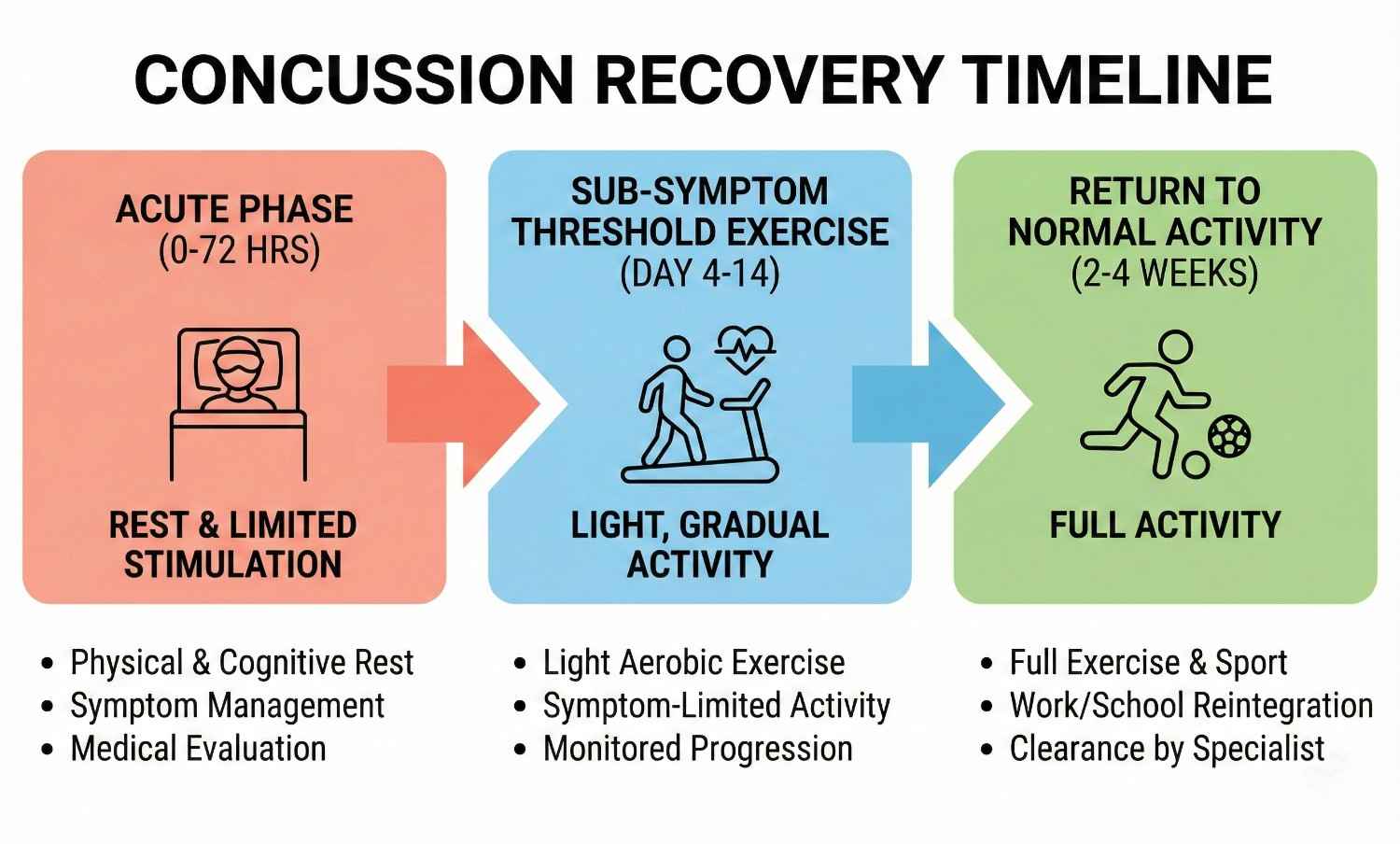

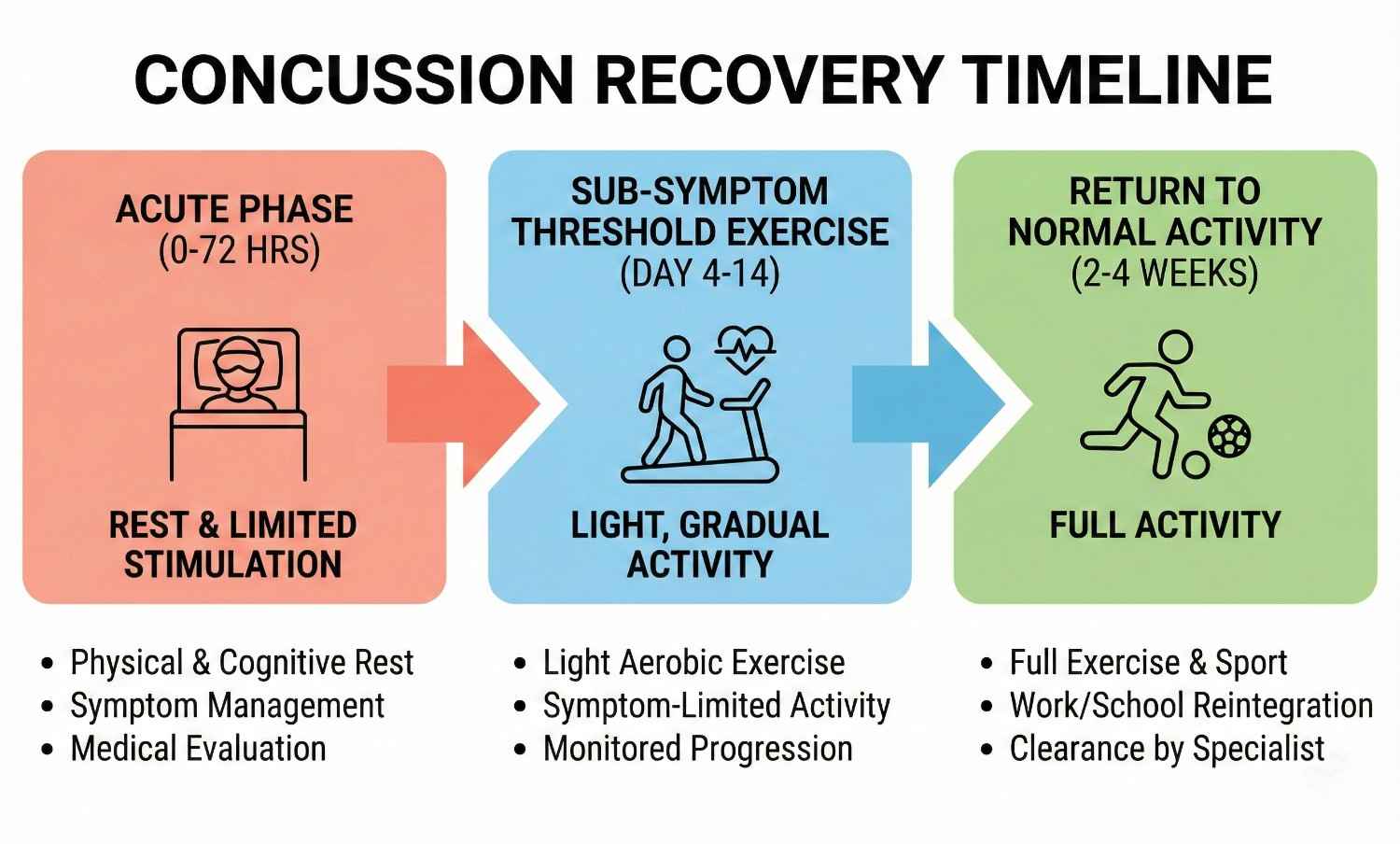

AccidentDoc Pasadena employs evidence-based treatment protocols progressing through four phases based on injury severity and patient response. All treatment is available through Letter of Protection, meaning $0 out-of-pocket cost until your case settles.

Phase 1 (Acute: Days 1-14) focuses on pain control and inflammation reduction. We prescribe NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) like ibuprofen or naproxen to reduce inflammation and pain. Muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine or tizanidine address muscle spasms. Ice application (15-20 minutes every 2-3 hours) reduces inflammation in the first 48-72 hours, then alternating ice/heat improves muscle relaxation. Soft cervical collars are used judiciously for 3-5 days maximum, as prolonged use causes muscle deconditioning. We emphasize active recovery over immobilization, encouraging gentle range of motion within pain tolerance.

Phase 2 (Subacute: Weeks 2-8) introduces active rehabilitation. Physical therapy includes cervical stretching exercises (chin tucks, corner stretches), progressive strengthening of deep neck flexors and stabilizers, postural training to correct forward head posture common in whiplash patients, and manual therapy including soft tissue mobilization. Chiropractic care with gentle cervical adjustments restores normal joint mobility, particularly at C5-C6 and C6-C7 where restriction commonly occurs. We use flexion-distraction techniques and activator methods rather than high-velocity rotational manipulation in acute whiplash. Massage therapy addresses myofascial trigger points in upper trapezius, levator scapulae, and suboccipital muscles that develop secondary to initial injury.

Phase 3 (Intermediate: Weeks 8-16) employs interventional procedures for patients not achieving adequate relief from conservative care. Trigger point injections deliver local anesthetic and sometimes corticosteroid to hyperactive muscle knots, providing immediate pain relief and allowing progression of physical therapy. Facet joint injections target the cervical zygapophyseal joints with fluoroscopically-guided anesthetic and steroid, diagnostic and therapeutic for facet-mediated pain. Medial branch blocks anesthetize the nerves supplying facet joints; positive response (>80% pain relief) predicts success with radiofrequency ablation for long-term pain control. Epidural steroid injections address cervical radiculopathy from disc herniation or foraminal stenosis, delivering anti-inflammatory medication directly to the inflamed nerve root.

Phase 4 (Surgical: Rarely Needed) is reserved for severe cases with progressive neurological deficits, confirmed structural pathology (large disc herniation compressing spinal cord or nerve root), or failure of 6+ months of comprehensive conservative care. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) removes herniated disc material and fuses adjacent vertebrae, reliably decompressing neural structures. Artificial disc replacement preserves motion at the surgical level, potentially reducing adjacent segment degeneration. Surgical intervention is appropriate for less than 5% of whiplash patients; our goal is always maximum recovery through non-surgical means.

Our treatment selection is individualized based on Quebec Task Force Classification, presence of radiculopathy, patient functional goals, and response to initial interventions. We provide comprehensive documentation for your attorney including causation analysis, treatment plans, and prognosis statements.

Acute Phase (Days 1-14)

1-2 weeksPain control, inflammation reduction, gentle mobility. NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, ice/heat therapy, soft collar (3-5 days max). Active recovery emphasis.

Subacute Phase (Weeks 2-8)

2-8 weeksActive rehabilitation with physical therapy, chiropractic adjustments, massage therapy. Progressive strengthening, range of motion restoration, postural correction.

Intermediate Phase (Weeks 8-16)

8-16 weeksInterventional procedures for persistent pain. Trigger point injections, facet joint injections, medial branch blocks, epidural steroid injections.

Surgical Phase (If Needed)

Case dependentReserved for progressive neurological deficits or failed conservative care. ACDF or artificial disc replacement. Less than 5% of cases.

Whiplash recovery follows predictable patterns correlated with injury severity, though individual variability exists based on age, pre-existing conditions, accident biomechanics, and treatment compliance. Understanding expected recovery timelines helps patients maintain realistic expectations and adhere to treatment protocols.

Grade 1 whiplash (neck pain without objective musculoskeletal signs) typically resolves in 6-12 weeks with conservative care. These patients experience complete functional recovery and return to pre-injury activities without restrictions. Pain decreases progressively with occasional minor flares during physical therapy progression.

Grade 2 whiplash (neck pain with musculoskeletal signs like restricted range of motion or point tenderness) requires 3-6 months for substantial recovery. Most patients achieve 80-90% improvement by 3 months with appropriate treatment, with residual symptoms manageable through self-care. Return to work occurs at 4-8 weeks depending on job demands—sedentary work earlier than labor-intensive positions. Functional capacity evaluations at 8-12 weeks objectively document work capabilities.

Grade 3 whiplash (neck pain with neurological signs including radiculopathy or cord compression) demands 6-12+ months for recovery, with some patients experiencing permanent limitations. Neurological recovery progresses slower than musculoskeletal healing; nerve regeneration occurs at approximately 1mm per day. Patients with confirmed nerve root compression may require 4-6 months to regain normal strength and sensation even after successful treatment. A subset develops chronic whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) with persistent symptoms beyond 6 months, requiring ongoing pain management and functional restoration.

Factors predicting prolonged recovery include high initial pain intensity (VAS >6/10), rapid onset of symptoms (<24 hours), presence of radicular symptoms, older age (>40 years), female gender (smaller neck musculature provides less protection), pre-existing cervical degenerative changes, rear-end collision mechanism, and delayed treatment initiation (>72 hours post-injury). Conversely, early mobilization, compliance with physical therapy, psychological resilience, and prompt treatment access predict favorable outcomes.

Recovery milestones we monitor include pain reduction (50% improvement by 4-6 weeks), range of motion improvement (within 10% of normal by 8 weeks), functional capacity (return to daily activities by 8-12 weeks), and return to work (light duty by 4-6 weeks, full duty by 8-16 weeks for most occupations). Our treatment approach accelerates progress through these milestones while preventing chronic pain development through comprehensive care addressing all injury components.

Comprehensive medical documentation is crucial for personal injury claims, insurance negotiations, and potential litigation. AccidentDoc Pasadena provides detailed documentation specifically designed for legal proceedings, going beyond standard medical records to establish causation, document disability, and support damages claims.

Our initial evaluation documents the accident mechanism in detail, correlating biomechanical forces with observed injuries. We note the specific collision type (rear-end, side-impact, frontal), estimated speed if known, whether the patient was aware of impending impact (bracing muscles provides some protection), seatbelt use, airbag deployment, vehicle damage, and whether the patient could drive away or required ambulance transport. This narrative establishes the temporal relationship between accident and injury onset, critical for proving causation.

Physical examination findings are documented with specificity: cervical range of motion measured in degrees using goniometry (normal: flexion 50°, extension 60°, rotation 80°, lateral flexion 45°), exact location of muscle tenderness and spasm, vertebral point tenderness at specific levels (e.g., "exquisite tenderness to palpation over C5 and C6 spinous processes"), neurological examination results including specific myotomes and dermatomes affected, and positive provocative tests with descriptions (e.g., "Spurling's test right side reproduced right arm radicular pain in C6 distribution").

Diagnostic imaging results are incorporated with clinical correlation: "MRI cervical spine dated [DATE] reveals C5-C6 disc herniation with rightward lateral component causing moderate right neural foraminal stenosis, consistent with patient's C6 radiculopathy characterized by right arm pain, biceps weakness, and diminished sensation over the radial forearm." This correlation between imaging findings and clinical presentation strengthens causation arguments.

Treatment plans document not just what we're doing but why: "Patient requires physical therapy 3x weekly for 8 weeks to restore normal cervical lordosis, improve deep neck flexor strength, and address myofascial trigger points. Failure to treat comprehensively risks chronic pain syndrome development." Progress notes document objective functional improvements: "Cervical rotation improved from 40° to 65° bilaterally. Patient now able to check blind spots while driving, previously impossible."

Causation statements explicitly link injuries to the accident: "It is my professional opinion within a reasonable degree of medical certainty that this patient's cervical spine injuries including C5-C6 disc herniation, cervical facet syndrome, and myofascial pain syndrome are directly and proximately caused by the motor vehicle collision of [DATE]. The documented mechanism (rear-end collision with sudden hyperextension-hyperflexion) is consistent with and sufficient to cause the observed injuries."

Disability ratings and restrictions are provided when maximum medical improvement (MMI) is reached: "Patient has reached MMI with 15% permanent partial impairment of the cervical spine per AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th Edition. Permanent restrictions include: no overhead work, no lifting >25 lbs, frequent breaks from static postures, no work requiring sustained neck rotation."

Prognostic statements inform settlement negotiations: "Patient likely requires ongoing pain management including occasional trigger point injections and maintenance physical therapy. Future medical costs estimated at $2,500-3,500 annually. Risk of accelerated cervical degenerative changes (post-traumatic arthritis) is moderate to high, potentially requiring surgical intervention in 10-15 years."

We also provide expert witness testimony when needed, appearing for depositions or trial testimony to explain injuries, treatment, causation, and prognosis to attorneys, insurance adjusters, and juries. Our documentation is prepared with litigation in mind from day one, ensuring your attorney has the strongest possible medical evidence supporting your claim.

- Detailed accident mechanism documentation correlating forces with injuries

- Objective physical examination findings with measurements and specific locations

- Diagnostic imaging results with clinical correlation to symptoms

- Comprehensive treatment plans with medical necessity justification

- Causation statements linking injuries to accident within reasonable medical certainty

- Disability ratings using AMA Guides when at maximum medical improvement

- Work restrictions and functional capacity documentation

- Prognosis statements including future medical needs and costs

- Expert witness availability for depositions and trial testimony

While most whiplash injuries are managed on an outpatient basis through our clinic, certain symptoms indicate potentially serious complications requiring emergency department evaluation. Patients and family members should be educated to recognize these red flags and seek immediate care when present.

Neurological emergency signs include progressive arm numbness or weakness (suggests worsening nerve root compression or spinal cord injury), bilateral arm symptoms (indicates central spinal cord involvement rather than isolated nerve root), bowel or bladder dysfunction including urinary retention or incontinence (cauda equina syndrome or central cord syndrome), lower extremity weakness or numbness (cervical myelopathy from spinal cord compression), and difficulty with balance or coordination (posterior column involvement or vertebral artery injury).

Vascular emergency signs include severe headache with sudden onset reaching maximum intensity within seconds ("thunderclap headache" suggests vertebral artery dissection or subarachnoid hemorrhage), headache with vision changes such as double vision, visual field cuts, or transient blindness (posterior circulation stroke from vertebral artery injury), dizziness with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), dysarthria (slurred speech), or facial numbness (brainstem stroke), and Horner's syndrome (ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis indicating sympathetic chain disruption from carotid or vertebral artery dissection).

Infectious warning signs include fever >101°F with neck pain and stiffness (meningitis, though rare after trauma), increasing pain despite treatment with constitutional symptoms like fever and night sweats (discitis or epidural abscess, typically developing weeks after penetrating injury or iatrogenic seeding).

Structural instability signs include severe pain with any neck movement suggesting instability, palpable cervical deformity or step-off (fracture-dislocation), and severe pain that is completely unrelenting despite all conservative measures (possible occult fracture).

When any of these red flag symptoms develop, we instruct patients to proceed immediately to the emergency department, preferably one with neurosurgery capabilities. Memorial Hermann Southeast Hospital, Houston Methodist Baytown Hospital, and Clear Lake Regional Medical Center all have neurosurgical coverage and advanced imaging available 24/7. After emergency stabilization and treatment, patients return to our care for ongoing management coordinated with the emergency intervention.

- Progressive arm numbness, weakness, or bilateral arm symptoms (nerve/cord injury)

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction - urinary retention or incontinence (cauda equina)

- Lower extremity weakness or numbness (cervical myelopathy)

- Sudden severe "thunderclap" headache (vertebral artery dissection)

- Headache with vision changes, double vision, or visual field defects (stroke)

- Dizziness with swallowing difficulty, slurred speech, or facial numbness (brainstem)

- Horner's syndrome - drooping eyelid, small pupil, no sweating on one side (arterial injury)

- Fever >101°F with neck stiffness (infection)

- Severe unrelenting pain despite all treatments (possible fracture)

- Difficulty with balance or coordination (posterior column or cerebellar involvement)

While many accidents are unavoidable, certain strategies reduce whiplash risk and severity. Proper headrest positioning is critical: the headrest should be adjusted so its top is level with the top of your head, positioned 2-3 inches from the back of your skull. This minimizes head travel distance during rear-end impacts. Studies show optimal headrest position reduces whiplash risk by up to 40%.

Maintaining good posture while driving—sitting upright with ears aligned over shoulders rather than forward head posture—provides better cervical spine alignment to withstand impact forces. Strengthening neck muscles through targeted exercises creates muscular protection. Awareness of surroundings and anticipating potential collisions allows protective muscle bracing, though this requires seeing the impending impact.

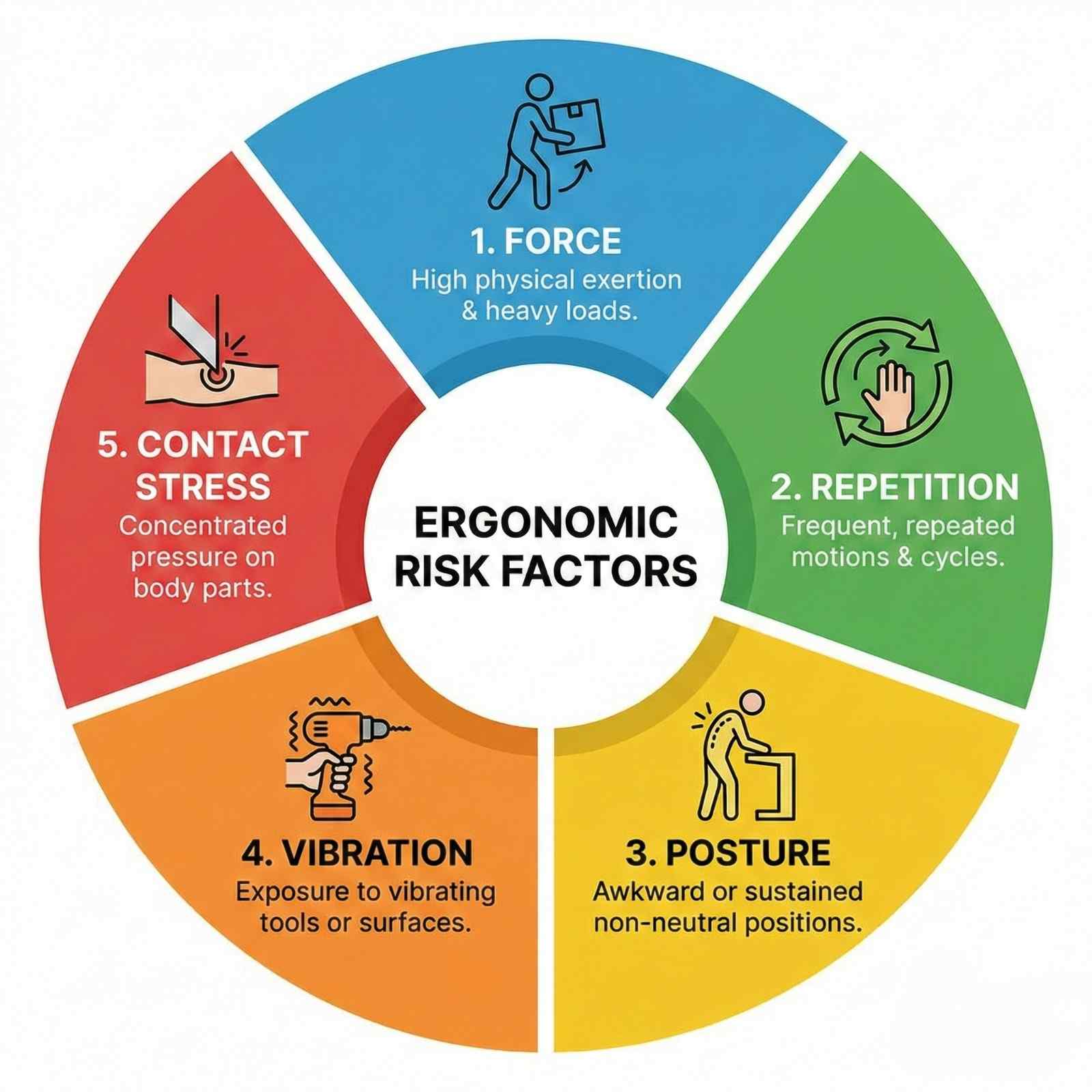

Post-injury self-care accelerates recovery: maintain gentle activity rather than prolonged immobilization, perform prescribed home exercises consistently, apply ice/heat as directed (ice for acute flares, heat for chronic stiffness), practice good sleep posture using cervical contour pillows, avoid prolonged static postures like computer work without breaks, and attend all scheduled therapy appointments. Ergonomic workstation setup prevents symptom exacerbation in office workers: monitor at eye level, keyboard positioned to keep elbows at 90°, lumbar support, and frequent posture changes every 30 minutes. These strategies combined with our comprehensive treatment approach optimize recovery and prevent chronic disability.

Seek Emergency Care Immediately If You Experience:

- Progressive arm numbness, weakness, or bilateral arm symptoms

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction (urinary retention or incontinence)

- Sudden severe "thunderclap" headache with vision changes

- Dizziness with difficulty swallowing or slurred speech

- Fever >101°F with neck stiffness

- Horner's syndrome (drooping eyelid, small pupil, facial asymmetry)

- Lower extremity weakness or difficulty walking

- Severe unrelenting pain despite all treatment measures

Call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room immediately

Back Pain & Spinal Injuries

Lower back pain affects 80% of Americans at some point in their lives, with car accidents, workplace injuries, and slip-and-falls being leading causes of acute spinal trauma. The lumbar spine bears tremendous compressive and rotational forces during accidents, making it vulnerable to disc herniations, facet joint injuries, and muscular strains. AccidentDoc Pasadena's physicians employ comprehensive diagnostic and treatment protocols to address both acute injury and prevent chronic disability.

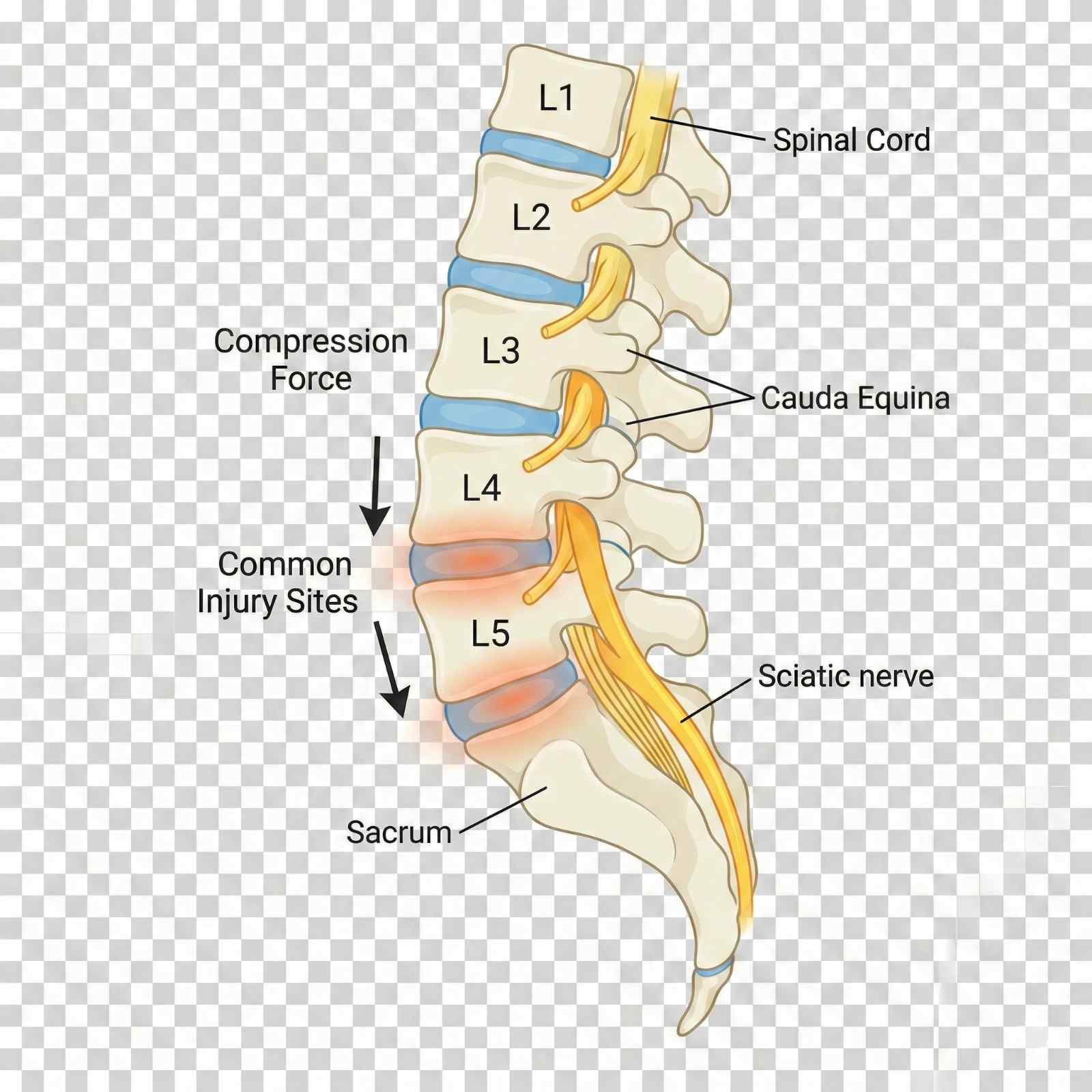

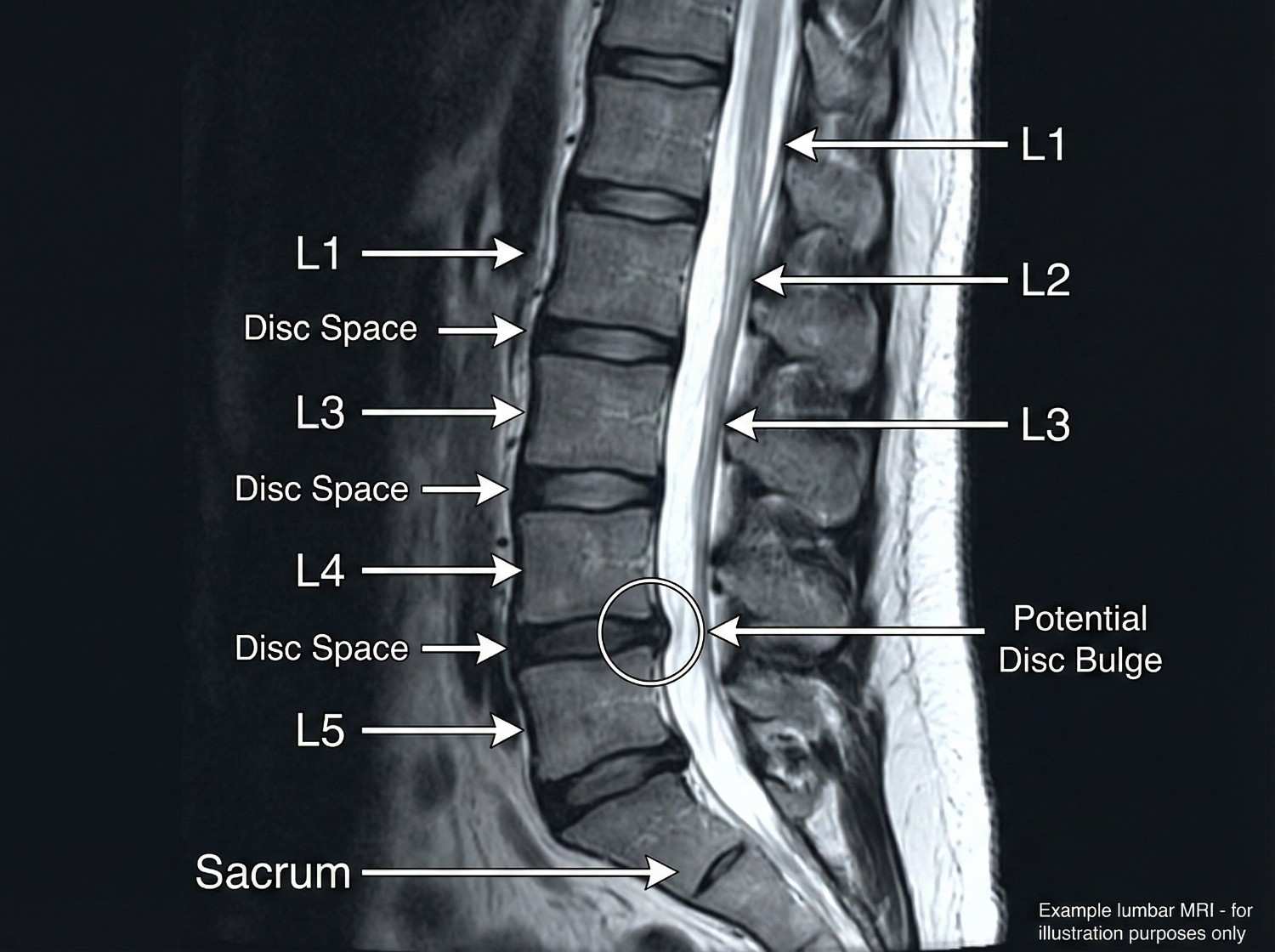

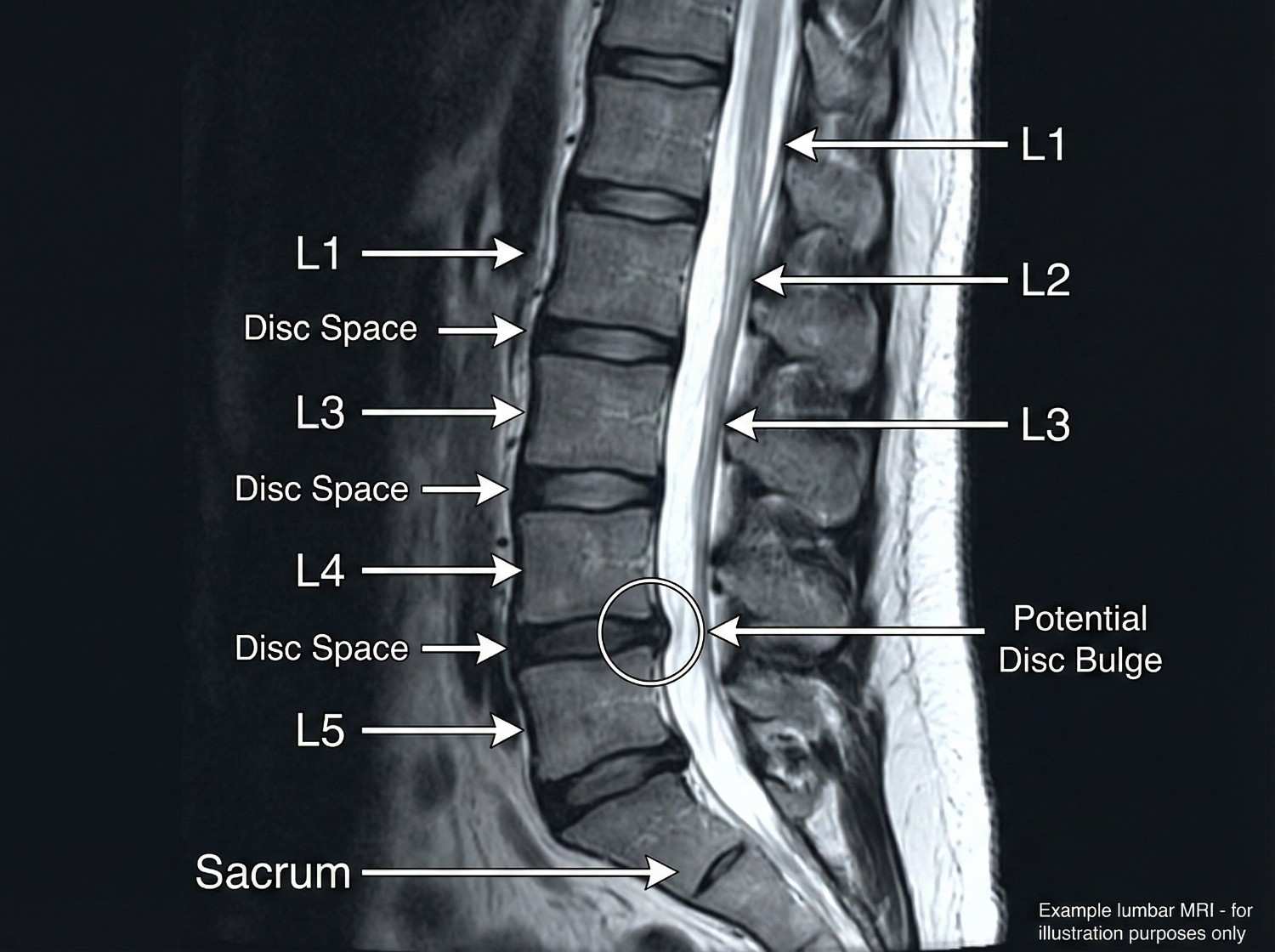

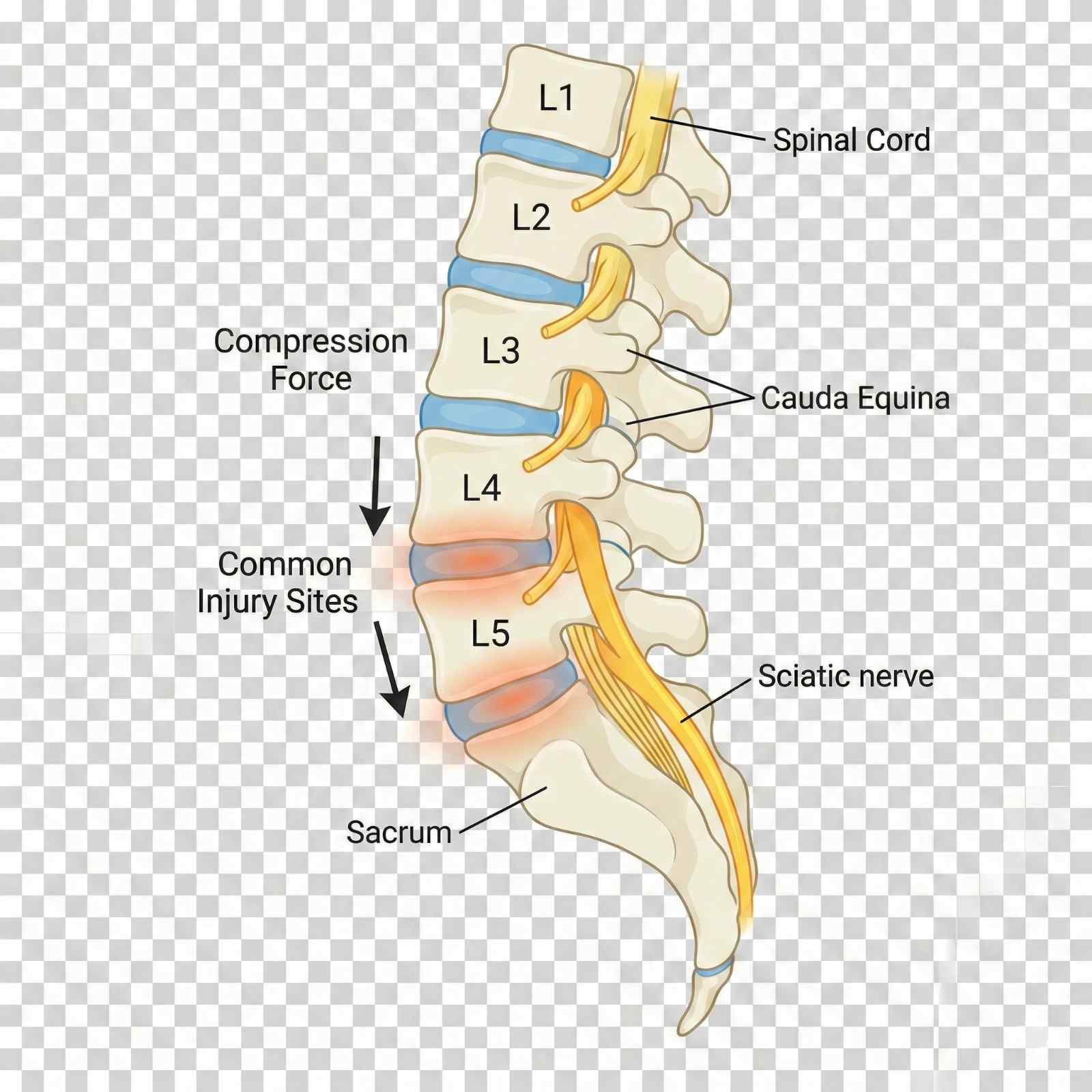

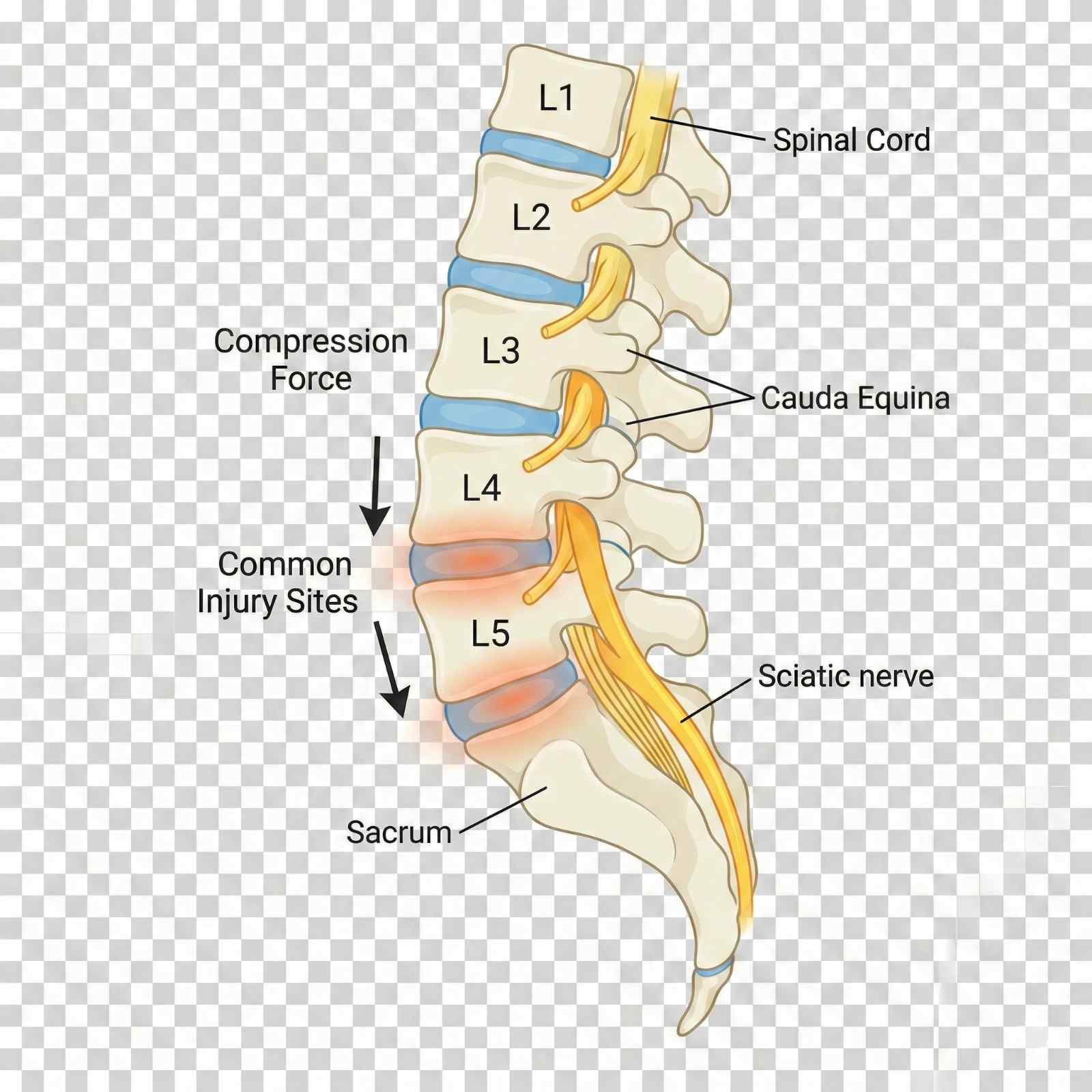

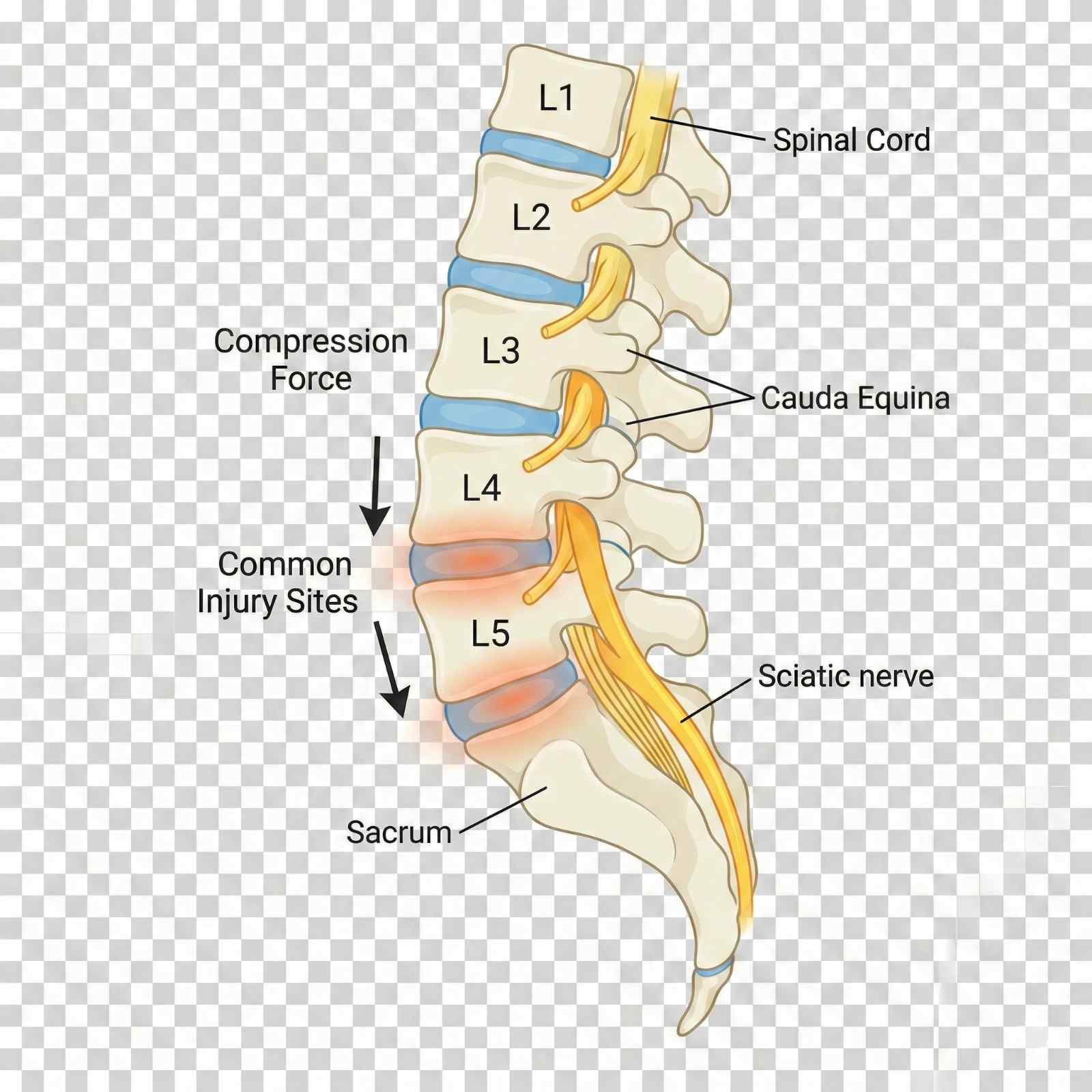

The lumbar spine consists of five vertebrae (L1-L5) plus the sacrum (S1), bearing the body's full weight during standing, walking, and lifting. Each motion segment includes the vertebral body, intervertebral disc, paired facet joints, ligamentous structures (anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, ligamentum flavum, interspinous and supraspinous ligaments), and surrounding musculature (erector spinae, multifidus, transversospinalis). The spinal canal houses the conus medullaris (spinal cord ending at L1-L2) and cauda equina (nerve roots L2-S5), with nerve roots exiting through neural foramina at each level.

Intervertebral discs are the spine's primary shock absorbers, consisting of a gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded by the tough annulus fibrosus. During compression forces typical of car accidents—particularly rear-end collisions where the torso is thrown into the seatback—the nucleus pulposus experiences tremendous pressure. If annular fibers are weakened by age-related degeneration or suddenly overloaded, the nucleus can herniate through the annular tear, typically in a posterolateral direction where annular fibers are thinnest and posterior longitudinal ligament support is minimal.

Facet joints are true synovial joints located posteriorly at each spinal level, guiding and limiting spinal motion. They are richly innervated by medial branch nerves and can generate significant pain when injured through capsular tears, cartilage damage, or inflammation. Rotational injuries during side-impact collisions or slip-and-falls particularly stress facet joints, as they limit rotational motion in the lumbar spine.

The L4-L5 and L5-S1 motion segments experience the greatest biomechanical stress due to their position at the lumbosacral junction, where the lumbar spine meets the relatively immobile sacrum. Approximately 95% of lumbar disc herniations occur at these two levels. The L5 nerve root (exiting at L4-L5) and S1 nerve root (exiting at L5-S1) are most commonly compressed, producing characteristic sciatica patterns: L5 radiculopathy causes dorsiflexion weakness (foot drop), lateral leg and dorsal foot numbness, and pain radiating down the posterior thigh and lateral leg. S1 radiculopathy causes plantarflexion weakness (difficulty standing on toes), posterior leg and plantar foot numbness, and pain radiating down the posterior leg to the heel.

Musculoligamentous injuries occur when sudden forces exceed tissue tolerances: multifidus and erector spinae muscles undergo eccentric overload during sudden deceleration, producing tears ranging from microscopic fiber disruption to complete muscle rupture. Ligamentous injuries involve the posterior ligamentous complex (supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, ligamentum flavum) and can create subtle spinal instability not always visible on static imaging.

Compressive loading from rear-end and frontal collisions represents the most common mechanism of lumbar injury in motor vehicle accidents. When the vehicle suddenly decelerates, the torso continues forward until restrained by the seatbelt, creating compressive and flexion forces on the lumbar spine. These forces can exceed 3,000 Newtons, sufficient to cause annular tears and disc herniations. The L4-L5 disc, positioned at the apex of lumbar lordosis, experiences maximal stress and is most frequently injured.

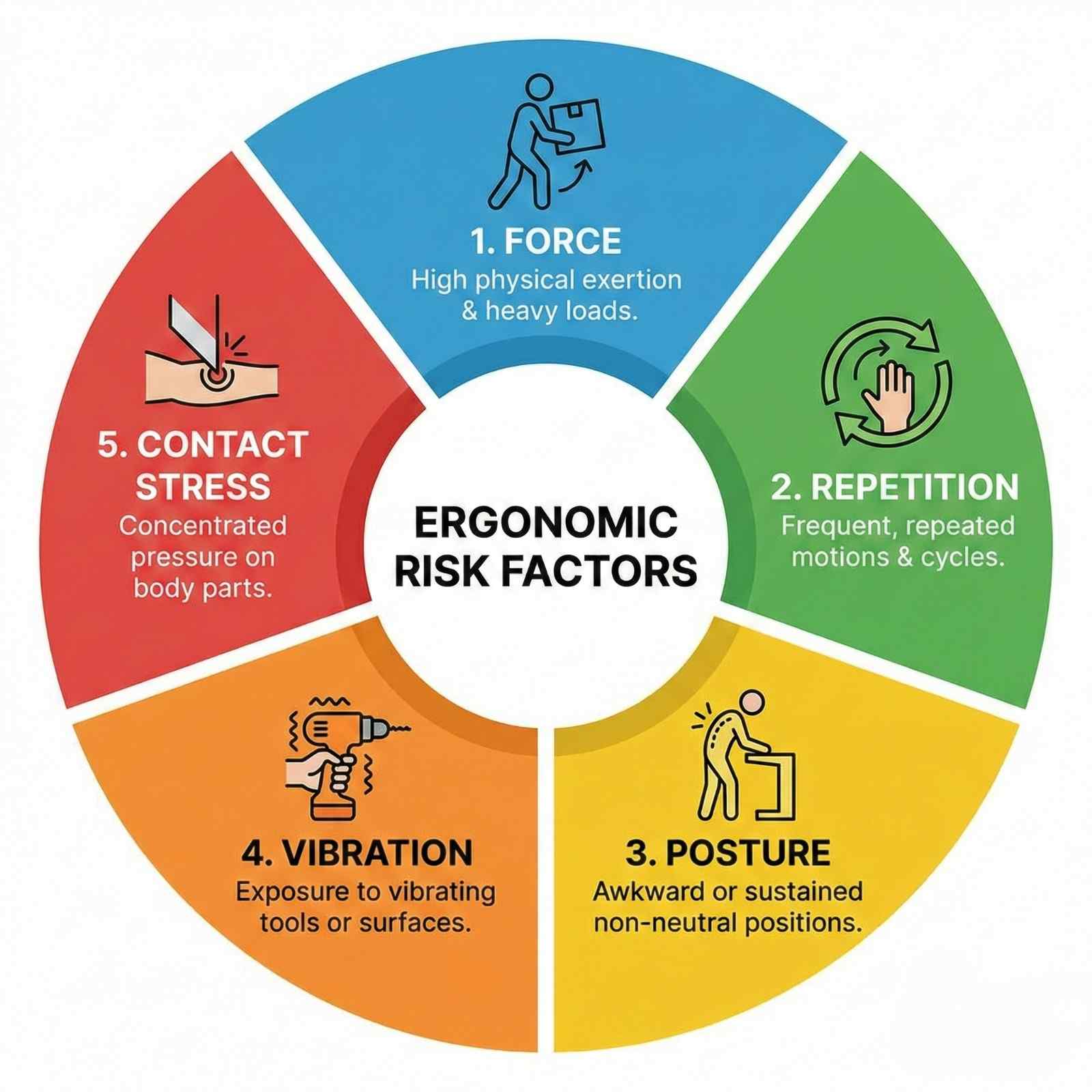

Lifting injuries in workplace settings account for substantial lumbar spine trauma, particularly in warehouse, construction, and healthcare workers. Improper lifting mechanics—bending at the waist rather than knees, twisting while lifting, or sudden unexpected loads—create asymmetric compressive and rotational forces exceeding disc and ligament tolerances. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) estimates that overexertion injuries, primarily lumbar strain and disc injuries, cost American businesses $15.1 billion annually in workers' compensation claims.

Slip-and-fall accidents generate unique injury patterns depending on landing position: landing on the buttocks creates axial loading through the sacrum, potentially causing sacral fractures, L5-S1 disc injury, or compression fractures in osteoporotic vertebrae. Landing on the side produces lateral compression and rotational forces, injuring facet joints and causing transverse process fractures. The sudden unexpected nature of falls prevents protective muscle activation, allowing full force transmission to skeletal structures.

Repetitive bending, twisting, and lifting in occupations like construction, refinery work, and warehouse operations causes cumulative trauma to lumbar discs. Each loading cycle causes microscopic annular fiber tears; when accumulated over months to years, these coalesce into macroscopic defects allowing nuclear herniation. Even without a specific acute event, workers develop symptomatic disc herniations that are compensable under Texas workers' compensation law as cumulative trauma injuries.

In Pasadena's industrial corridor along Highway 225, refinery and petrochemical workers experience unique mechanisms including falls from height, being struck by falling equipment or materials, and crush injuries from machinery. These high-energy mechanisms often cause multiple-level injuries, fractures, and combined bone-soft tissue trauma requiring comprehensive multidisciplinary care.

- Motor vehicle accidents (rear-end and frontal) - compression and flexion forces

- Lifting injuries with improper mechanics - twisting, bending, unexpected loads

- Slip-and-fall on buttocks - axial loading through sacrum to L5-S1

- Repetitive occupational bending and lifting - cumulative disc trauma

- Falls from height - high-energy compression and fracture risk

- Industrial accidents - crush injuries, being struck by objects

- 18-wheeler accidents - severe multi-level injuries from high forces

Lumbar spine injury symptoms range from localized mechanical back pain to severe radiculopathy with neurological deficits, depending on involved structures. Understanding this symptom spectrum guides diagnostic workup and treatment selection.

Mechanical low back pain from muscular strain and facet joint injury manifests as localized lumbar discomfort, often described as deep aching or sharp with movement. Pain worsens with extension (bending backward, overhead reaching) in facet-mediated pain, and with flexion (forward bending, sitting) in discogenic pain. Muscle spasm is palpable as firm, tender bands in the paraspinal muscles, representing protective guarding. Range of motion is restricted, particularly in the direction stressing injured structures. Mechanical pain typically remains localized to the back and buttocks without leg radiation.

Sciatica, the hallmark of nerve root compression, presents as sharp, burning, or electric pain radiating from the lower back down the posterior or lateral thigh, through the calf, and into the foot. The pain distribution follows specific dermatomal patterns: L5 radiculopathy produces lateral leg and dorsal foot pain, while S1 radiculopathy causes posterior leg and plantar foot pain. Patients often describe the pain as "shooting" or "like an electric shock," distinctly different from muscular aching. The pain intensity often exceeds back pain, and patients report that leg pain is their primary complaint.

Neurological symptoms accompany more severe nerve compression: numbness or paresthesias (tingling) in dermatomal distributions, weakness in specific muscle groups (L5: foot dorsiflexion and toe extension; S1: plantarflexion and toe flexion), and reduced or absent deep tendon reflexes (L5: medial hamstring; S1: Achilles). These neurological deficits indicate need for prompt MRI and potentially urgent intervention if progressive.

Cauda equina syndrome represents a surgical emergency requiring immediate decompression, characterized by bilateral leg symptoms, saddle anesthesia (numbness in the perineal region), bowel or bladder dysfunction (urinary retention most common initially, followed by overflow incontinence), and progressive bilateral leg weakness. Though rare (occurring in 1-2% of large disc herniations), cauda equina syndrome risk necessitates education of all patients with severe sciatica about warning signs.

Delayed symptom onset is common in lumbar injuries: patients may feel "fine" immediately after accidents, only to develop severe pain 24-48 hours later as inflammation peaks. This delayed onset doesn't invalidate causation—it reflects the natural inflammatory timeline following soft tissue injury.

| Symptom | Timing / Description |

|---|---|

| Localized low back pain | Immediate to Delayed |

| Pain with forward bending | Immediate to Delayed |

| Pain with backward bending | Immediate to Delayed |

| Sciatica (leg pain) | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| Leg numbness/tingling | Delayed to Chronic |

| Foot drop (L5) | Delayed to Chronic |

| Difficulty standing on toes (S1) | Delayed to Chronic |

| Reduced reflexes | Delayed to Chronic |

| Bilateral leg symptoms | Emergency |

| Bowel/bladder dysfunction | Emergency |

Comprehensive diagnostic evaluation combines clinical assessment with targeted imaging to identify all injured structures and guide treatment decisions. Our systematic approach ensures accurate diagnosis while avoiding unnecessary testing.

Clinical examination begins with observing gait, posture, and spinal contour—loss of normal lumbar lordosis suggests muscle spasm and protective guarding. Active range of motion testing quantifies functional limitations: forward flexion (normal: fingers to floor or within 10cm), extension (normal: 25-30°), lateral flexion (normal: 25-30° each side), and rotation (normal: 30-45° each direction, though limited in lumbar spine). We use goniometry or inclinometry for objective documentation supporting disability ratings.

Palpation identifies point tenderness over spinous processes (suggesting fracture, ligament injury, or facet pathology), paraspinal muscle spasm and trigger points, and sacroiliac joint tenderness (commonly injured in falls on buttocks). Percussion over spinous processes elicits pain in vertebral fractures. Straight leg raise test (SLR) is the gold standard provocative maneuver for lumbar radiculopathy: with the patient supine, we slowly raise the extended leg; pain radiating below the knee between 30-70° of elevation indicates nerve root tension, highly specific for disc herniation when the pain is reproduced in the contralateral leg (crossed SLR). Femoral nerve stretch test (patient prone, knee flexed, hip extended) reproduces anterior thigh pain in upper lumbar radiculopathy (L2-L4).

Neurological examination systematically assesses motor function (manual muscle testing of hip flexors L2, quadriceps L3/L4, ankle dorsiflexion L5, ankle plantarflexion S1), sensory function (light touch and pinprick in all dermatomes), and reflexes (patellar L4, medial hamstring L5, Achilles S1). Documentation notes specific findings: "4/5 strength ankle dorsiflexion right, 2+ Achilles reflex left vs 0 right, sensory deficit plantar foot S1 distribution right—consistent with S1 radiculopathy."

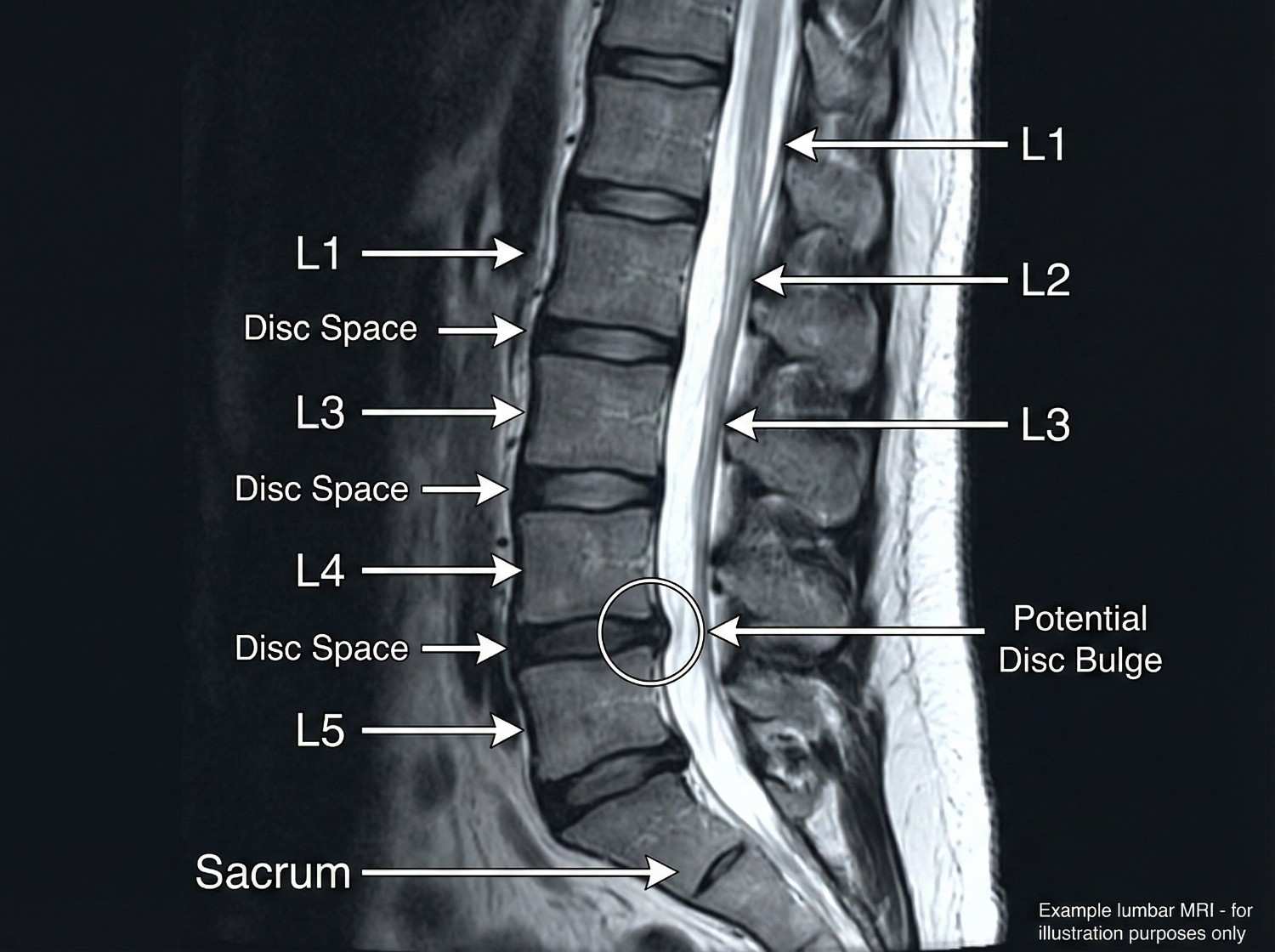

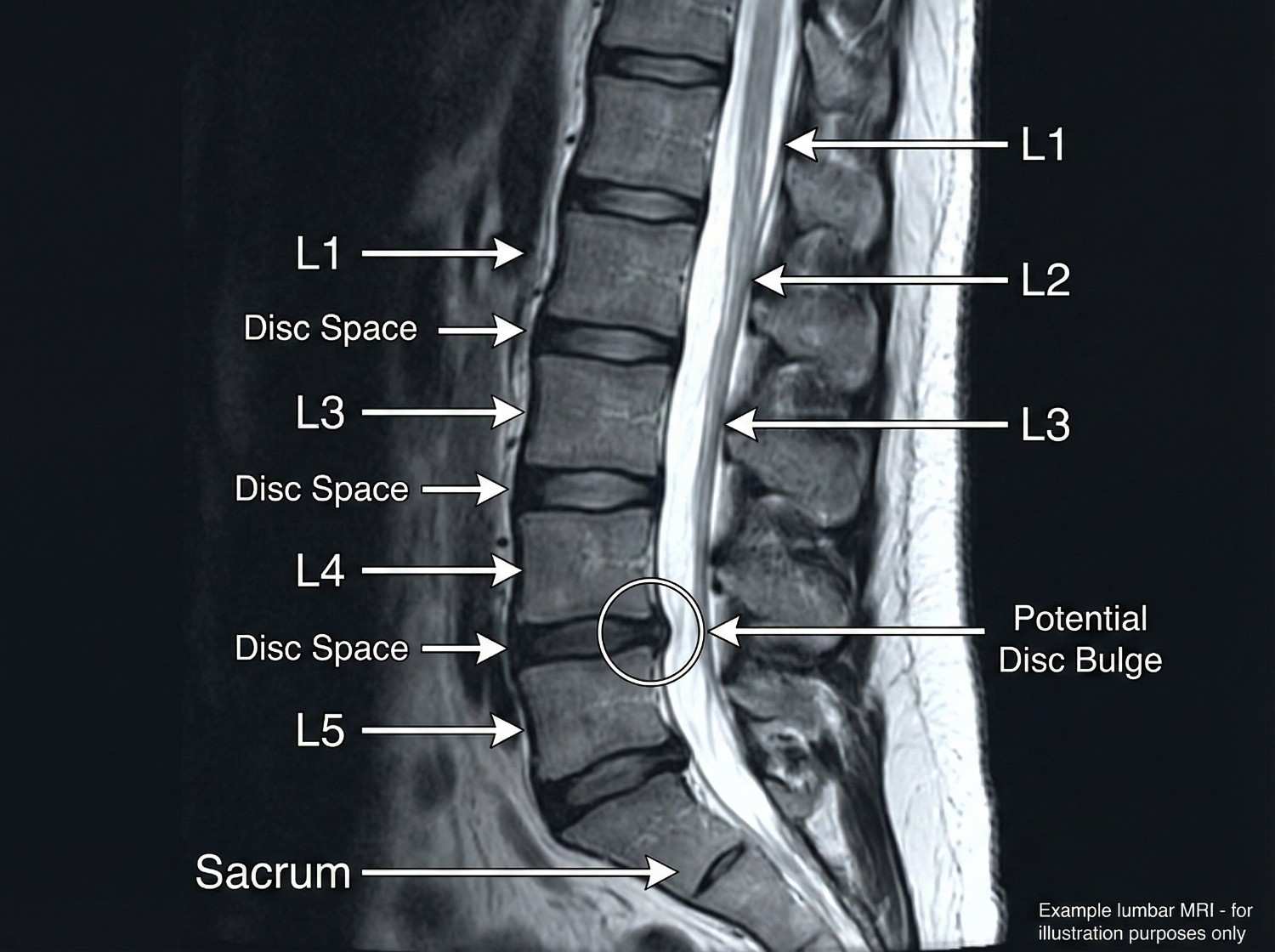

Imaging selection follows evidence-based guidelines: Lumbar X-rays (AP and lateral views) are initial studies to assess alignment, measure disc space heights (narrowing suggests degeneration), identify fractures or spondylolisthesis (vertebral slippage), and evaluate for degenerative changes. Flexion-extension views assess spinal stability when ligamentous injury is suspected. X-rays have limited utility for soft tissue evaluation but are valuable for initial screening.

MRI lumbar spine without contrast is the definitive study for disc herniations, nerve root compression, spinal stenosis, ligamentous injuries, and bone marrow edema indicating fractures. We order MRI when radicular symptoms exist, neurological deficits are present, severe pain persists beyond 4-6 weeks of conservative care, or red flag symptoms suggest serious pathology (cauda equina, infection, malignancy). MRI findings are correlated with clinical presentation—incidental disc bulges without nerve compression don't explain radicular symptoms, while a right posterolateral disc herniation compressing the right S1 nerve root perfectly explains right S1 radiculopathy.

CT scanning provides superior bony detail for fractures, pars defects (spondylolysis), and bony stenosis, but lacks MRI's soft tissue resolution. CT myelography (CT after intrathecal contrast injection) is reserved for patients unable to undergo MRI (pacemakers, certain metal implants) when soft tissue visualization is necessary.

Electrodiagnostic studies (EMG/NCS) performed 3-4 weeks post-injury detect physiological nerve injury even when MRI shows anatomical compression. Abnormal findings include fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves (denervation), reduced motor unit recruitment (weakness), and slowed nerve conduction velocities. EMG differentiates radiculopathy from peripheral nerve entrapments (peroneal nerve palsy mimics L5 radiculopathy) and polyneuropathy.

Our evidence-based treatment protocols progress through phases based on injury severity, patient response, and functional goals. All care is available through Letter of Protection with $0 out-of-pocket cost.

Phase 1 (Acute: Days 1-10) emphasizes controlled activity, not bed rest. Research demonstrates that prolonged bed rest delays recovery and increases chronic pain risk; we recommend limiting bed rest to 2-3 days maximum. Activity modification avoids pain-provoking movements (heavy lifting, prolonged sitting, twisting) while maintaining general activity. Ice application (20 minutes every 2-3 hours) reduces inflammation in the first 48 hours, then alternating ice/heat provides symptomatic relief. Medication includes NSAIDs (ibuprofen 800mg TID or naproxen 500mg BID) for inflammation, muscle relaxants (cyclobenzaprine 5-10mg at bedtime, tizanidine 4mg TID) for muscle spasm, and neuropathic pain medications (gabapentin, pregabalin) for radiculopathy. Short-course oral corticosteroids (methylprednisolone dose pack) provide potent anti-inflammatory effect for severe radiculopathy.

Phase 2 (Subacute: Weeks 2-8) introduces active rehabilitation. Physical therapy employs multiple modalities: McKenzie method (repeated extension exercises) centralizes pain from the leg back to the central spine, indicating favorable prognosis; core stabilization strengthens transversus abdominis, multifidus, and other deep stabilizers that protect the spine; manual therapy including soft tissue mobilization and joint mobilization improves mobility; and functional training retrains proper movement patterns for daily activities and work tasks. A typical protocol involves 2-3 sessions weekly for 6-8 weeks.

Chiropractic care utilizes flexion-distraction technique (Cox technique) which gently stretches the lumbar spine, creating negative intradiscal pressure that may reduce disc herniations while mobilizing facet joints. High-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) adjustments restore normal joint motion in restricted segments. Side-posture manipulation is employed cautiously in acute disc herniation, prioritizing flexion-distraction initially. Treatment frequency typically starts at 3x weekly, tapering to 2x then 1x weekly as symptoms improve.

Massage therapy addresses secondary myofascial dysfunction: gluteus medius, piriformis, quadratus lumborum, and erector spinae often develop trigger points and hypertonicity secondary to primary lumbar pathology. Deep tissue massage, myofascial release, and trigger point therapy reduce muscle pain and improve flexibility, allowing more effective participation in strengthening exercises.

Phase 3 (Intermediate: Weeks 8-16) employs interventional procedures when conservative care provides inadequate relief. Epidural steroid injections are the gold standard for radiculopathy from disc herniation. Performed under fluoroscopic guidance, we deliver corticosteroid and local anesthetic directly to the inflamed nerve root via transforaminal (most specific, targets individual nerve root), interlaminar (midline approach, broader coverage), or caudal (through sacral hiatus, good for multi-level or S1 pathology) approaches. Success rates range from 50-70% for significant pain reduction lasting 3+ months, with best results in acute radiculopathy (<3 months duration) from contained disc herniations.

Facet joint injections target the zygapophyseal joints with fluoroscopically-guided injection of anesthetic and corticosteroid, both diagnostic (>80% pain relief confirms facet-mediated pain) and therapeutic. Medial branch blocks anesthetize the nerves innervating facet joints; patients achieving >80% pain relief for the duration of local anesthetic action are candidates for radiofrequency ablation. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses thermal energy to create controlled lesions in medial branch nerves, providing 6-12 months of pain relief with repeatability. RFA is particularly effective for chronic facet-mediated pain unresponsive to conservative care.

Trigger point injections deliver local anesthetic (and sometimes corticosteroid) to hyperactive muscle trigger points in paraspinal, gluteal, and piriformis muscles, providing immediate pain relief and allowing advancement of physical therapy. Sacroiliac joint injections address SI joint dysfunction common after falls on buttocks or asymmetric loading patterns.

Phase 4 (Surgical: When Conservative Care Fails) is considered after 6+ months of comprehensive non-surgical treatment without adequate improvement, or sooner if progressive neurological deficits, cauda equina syndrome, or severe functional impairment exist. Microdiscectomy is the gold standard for disc herniation with radiculopathy, involving microscopic removal of herniated disc material compressing the nerve root. Success rates exceed 85-90% for leg pain relief, though back pain improves less reliably. Laminectomy removes bone (lamina) to decompress spinal canal stenosis causing neurogenic claudication. Spinal fusion stabilizes painful motion segments using bone graft and instrumentation (pedicle screws and rods), appropriate for spondylolisthesis, instability, or severe degenerative disc disease after failed conservative care.

Acute Phase (Days 1-10)

1-10 daysControlled activity (bed rest <3 days), ice/heat, NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, neuropathic pain medication. Activity modification avoiding pain triggers.

Subacute Phase (Weeks 2-8)

2-8 weeksPhysical therapy (McKenzie method, core stabilization), chiropractic (flexion-distraction, HVLA), massage therapy for myofascial pain. 2-3x weekly.

Intermediate Phase (Weeks 8-16)

8-16 weeksInterventional procedures: epidural steroid injections, facet injections, medial branch blocks, radiofrequency ablation, trigger point injections.

Surgical Phase (If Needed)

Case dependentMicrodiscectomy for disc herniation, laminectomy for stenosis, fusion for instability. After 6+ months conservative care or if progressive neurological deficits.

Lumbar spine injury recovery varies significantly based on specific pathology, severity, patient age, baseline fitness, and psychosocial factors including job satisfaction and litigation status. Understanding expected timelines helps maintain realistic expectations.

Lumbar muscle strain (no radiculopathy, no disc herniation) typically resolves in 6-8 weeks with conservative care. Most patients achieve 80% improvement by 4 weeks, with residual discomfort managed through home exercise and occasional NSAIDs. Return to sedentary work occurs at 2-3 weeks with activity modification; return to heavy labor at 6-8 weeks with gradual job conditioning.

Lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy follows a longer course: natural history studies show that 60-70% of patients improve significantly with non-surgical care over 3-6 months. Initial severe leg pain typically improves first (within 4-8 weeks), followed by neurological recovery (strength, sensation) over 2-4 months. Approximately 10-15% of patients undergo surgery due to either failure of conservative care (persistent severe pain and disability) or progressive neurological deficits. Post-surgical recovery from microdiscectomy typically allows return to light work at 4-6 weeks, heavy work at 3 months, with continued improvement to one year.

Chronic low back pain (>3 months duration) requires multifaceted treatment addressing physical deconditioning, pain psychology, and functional restoration. Functional restoration programs combining intensive physical therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and work conditioning produce superior outcomes compared to passive treatment modalities, with 65-75% of patients returning to pre-injury work status within 6 months of program completion.

Spinal fusion recovery is prolonged: bony fusion consolidation requires 6-12 months, though functional recovery allows desk work at 6-8 weeks, light physical work at 3-4 months, and unrestricted activity at 6-9 months post-surgery. Fusion at one level increases adjacent segment stress by approximately 30-40%, potentially accelerating degeneration at adjacent levels with 20-30% of patients developing adjacent segment disease within 10 years.

Factors predicting prolonged recovery include high initial pain intensity, widespread pain beyond primary injury site, catastrophic thinking and fear-avoidance beliefs, job dissatisfaction or workplace conflict, pending litigation (though treatment shouldn't be delayed), smoking (impairs tissue healing), obesity (increases mechanical spine loading), and pre-existing degenerative changes. Conversely, positive prognostic factors include rapid initial improvement (>30% pain reduction in first 2 weeks), good treatment compliance, strong social support, satisfying job with supportive employer, non-smoking status, and healthy body weight.

We monitor specific functional milestones: walking tolerance (goal: 30+ minutes continuous), sitting tolerance (goal: 45-60 minutes before requiring position change), lifting capacity (progressively increasing from 5 lbs to job-specific requirements), and pain-free sleep. Functional capacity evaluations performed at 8-12 weeks objectively document work capabilities and restrictions, invaluable for workers' compensation and personal injury cases.

Comprehensive documentation for lumbar spine injuries requires correlation of mechanism, clinical findings, imaging results, and functional limitations. Our reports are specifically designed for legal proceedings, insurance negotiations, and workers' compensation claims.

Mechanism documentation establishes causation: "Patient sustained lumbar spine injury on [DATE] when struck from behind while stopped at traffic light on Red Bluff Road. The sudden deceleration and compressive loading of the lumbar spine in seated position is biomechanically consistent with and sufficient to cause the observed L5-S1 disc herniation." For workers' compensation cases: "Cumulative trauma from repetitive lifting of 50-75 lb boxes while employed as warehouse associate for [EMPLOYER] from 2020-2024 caused progressive annular deterioration and eventual L4-L5 disc herniation becoming symptomatic on [DATE]."

Physical examination findings are documented with quantification: "Lumbar forward flexion limited to 40° (normal 90°), extension 10° (normal 25°), right lateral flexion 15° (normal 25°). Positive straight leg raise test right side reproducing S1 radiculopathy at 35° elevation. Absent right Achilles reflex, 4/5 plantarflexion strength right, sensory deficit plantar foot S1 distribution. Positive facet loading test L4-L5 and L5-S1 bilaterally."

Imaging correlation strengthens causation arguments: "MRI lumbar spine dated [DATE] demonstrates large right posterolateral disc herniation at L5-S1 with moderate to severe right neural foraminal stenosis and displacement of the right S1 nerve root. These findings directly correlate with and explain the patient's clinical presentation of right S1 radiculopathy characterized by posterior leg pain radiating to heel, plantar foot numbness, reduced plantarflexion strength, and absent Achilles reflex."

Treatment documentation emphasizes medical necessity: "Patient requires epidural steroid injection at L5-S1 to reduce neural inflammation and facilitate participation in physical therapy. Conservative measures including 8 weeks of physical therapy, chiropractic care, and medication management have provided only partial relief (30% improvement per VAS). Without interventional treatment, patient faces high risk of chronic pain syndrome development and possible surgical necessity."

Causation opinions are stated clearly: "Within a reasonable degree of medical probability, this patient's L5-S1 disc herniation and resultant S1 radiculopathy are directly and proximately caused by the motor vehicle collision of [DATE]. The documented mechanism (sudden deceleration with compressive loading) is biomechanically consistent with disc herniation. The temporal relationship (symptoms developing within 24 hours of accident) supports causation. The patient had no prior history of lumbar radiculopathy or disc herniation, with prior medical records documenting only occasional mechanical back pain responsive to over-the-counter medication. The current condition represents new injury directly attributable to the accident."

Disability ratings using AMA Guides to Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th Edition, are provided at maximum medical improvement: "Patient has reached MMI 14 months post-injury after conservative care and one-level microdiscectomy. Residual findings include: 25% loss of lumbar range of motion, persistent 4+/5 ankle plantarflexion weakness right, diminished S1 dermatomal sensation. Using DRE (Diagnosis-Related Estimate) Category III (radiculopathy with objective findings), patient has 13% whole person impairment." Permanent restrictions guide return-to-work planning: "Permanent restrictions include: lifting limited to occasional 25 lbs, frequent 15 lbs; no repetitive bending or twisting; no prolonged static postures (sitting/standing >45 minutes without position change); no work requiring prolonged driving; no climbing ladders or scaffolds."

Future medical needs and costs are estimated: "Patient will require ongoing pain management including episodic physical therapy (estimated 8-12 sessions annually), periodic epidural injections (1-2 annually), medication management, and possible additional surgery if adjacent segment degeneration develops (20-30% risk over 10 years, estimated cost $75,000-100,000)."

Life care planning for catastrophic injuries documents all future medical, therapeutic, and supportive care needs with associated costs over the patient's remaining lifetime, supporting economic damages claims in personal injury litigation.

- Mechanism documentation establishing biomechanical causation

- Quantified physical examination with range of motion measurements

- Imaging findings correlated with clinical presentation

- Treatment plans with medical necessity justification

- Causation opinions stated within reasonable medical probability

- Disability ratings per AMA Guides at maximum medical improvement

- Permanent work restrictions for return-to-work and vocational assessment

- Future medical needs and costs for life care planning

- Expert witness testimony availability for depositions and trial

Certain lumbar spine injury presentations indicate surgical emergencies or serious underlying pathology requiring immediate advanced care. Patient education about these red flags is critical for preventing permanent disability.

Cauda equina syndrome is a neurosurgical emergency caused by massive central disc herniation or other space-occupying lesion compressing multiple nerve roots of the cauda equina. Classic presentation includes bilateral leg pain and weakness (distinguishing it from typical unilateral radiculopathy), saddle anesthesia (numbness in the perineal region, inner thighs, and buttocks—areas that would contact a saddle), and bowel/bladder dysfunction initially presenting as urinary retention (inability to void despite full bladder sensation), progressing to overflow incontinence and fecal incontinence. Sexual dysfunction is also common. Cauda equina requires emergency MRI and surgical decompression within 24-48 hours; delays beyond 48 hours are associated with significantly increased rates of permanent bowel/bladder dysfunction and sexual impairment. Any patient presenting with bilateral leg symptoms and saddle symptoms should proceed immediately to an emergency department with neurosurgical coverage.

Progressive motor weakness, particularly rapid progression or weakness affecting multiple myotomes bilaterally, suggests either cauda equina syndrome or conus medullaris syndrome (injury to the spinal cord terminus at L1-L2). Isolated foot drop (L5) developing or worsening despite treatment warrants urgent MRI and possible surgical consultation, as prolonged nerve compression beyond 6-8 weeks reduces likelihood of neurological recovery even after successful decompression.

Bowel or bladder changes including urinary retention (most sensitive early sign of cauda equina), new onset urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or loss of rectal tone (assessed by digital rectal examination in emergency department) all mandate emergency evaluation. Patients should be instructed that difficulty initiating urination or decreased awareness of bladder fullness warrants immediate ER evaluation.

Fever with back pain raises concern for spinal infection including discitis (disc space infection), osteomyelitis (vertebral body infection), or epidural abscess. Risk factors include diabetes, immunosuppression, IV drug use, recent spine procedure/injection, or penetrating injury. Spinal infections can progress rapidly to neurological compromise and sepsis; immediate evaluation with MRI and laboratory studies (white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, blood cultures) is essential.

Nocturnal pain worse than daytime pain, particularly pain that awakens the patient from sleep and is not relieved by any position, raises concern for neoplasm (primary spinal tumor or metastatic disease). Constitutional symptoms including unexplained weight loss, fever, night sweats, or history of cancer increase suspicion. These patients require prompt MRI to evaluate for pathologic fracture, epidural tumor, or metastatic disease.

Significant trauma, especially in elderly patients or those with known osteoporosis, risks vertebral compression fractures. Acute severe back pain after fall, motor vehicle accident, or other trauma warrants X-rays initially; MRI is added if neurological symptoms develop or if fracture involves the posterior vertebral body (risk of retropulsed fragments compressing neural elements).

When any red flag symptom develops, we direct patients to emergency departments with neurosurgical capabilities: Memorial Hermann Southeast, Houston Methodist Baytown, Clear Lake Regional Medical Center, or Ben Taub Hospital for indigent patients. After emergency stabilization, patients return to our clinic for coordinated ongoing care.

- Cauda equina syndrome - bilateral leg pain/weakness, saddle anesthesia, urinary retention - SURGICAL EMERGENCY

- Progressive motor weakness, especially bilateral or multi-level

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction - incontinence or retention

- Fever with back pain - suggests infection (discitis, epidural abscess)

- Nocturnal pain worse than daytime - concern for neoplasm

- Unexplained weight loss, night sweats - systemic disease

- Significant trauma in elderly/osteoporotic patients - fracture risk

- Pain unrelieved by any position or intervention - severe pathology

- Bilateral leg numbness or weakness - central compression

- Loss of rectal tone or anal sphincter control - cauda equina

While many lumbar injuries result from unavoidable accidents, risk reduction strategies and proper ergonomics minimize injury severity and prevent chronic disability. Proper lifting mechanics are fundamental: always bend at knees rather than waist, keep load close to body (increasing lever arm by holding load away from body exponentially increases lumbar compression forces), avoid twisting while lifting (rotational forces maximally stress annulus fibrosus), and test load weight before committing to the lift. OSHA recommends limiting repetitive lifting to 51 lbs maximum for most workers, with lower limits (25 lbs) for frequent lifting.

Workplace ergonomics modifications include adjustable-height workstations allowing sit-stand alternation for office workers, anti-fatigue mats for workers in static standing positions, mechanical lifting aids (forklifts, pallet jacks, hoists) for material handling, team lifts for loads exceeding individual safe lifting limits, and job rotation to vary physical demands and prevent cumulative trauma. Core strengthening through targeted exercises creates muscular protection: transversus abdominis and multifidus provide spinal stability, while erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and hip muscles contribute to load distribution. A basic core program includes planks, bird-dogs, dead bugs, and bridges performed 3-4x weekly.

Maintaining healthy body weight reduces chronic lumbar loading—each pound of excess abdominal weight creates amplified force on lumbar discs due to leverage effects. Smoking cessation improves disc nutrition (nicotine impairs blood flow to intervertebral discs) and enhances healing capacity. Post-injury, adherence to prescribed rehabilitation exercises prevents recurrence and chronic disability. Workplace accommodation through light duty assignments during recovery allows earlier return to work while respecting healing tissue limitations, reducing overall disability duration.

Seek Emergency Care Immediately If You Experience:

- Bilateral leg pain, weakness, or numbness (cauda equina syndrome)

- Saddle anesthesia - numbness in perineal area, inner thighs, buttocks

- Urinary retention, inability to void, or new incontinence

- Fecal incontinence or loss of bowel control

- Progressive motor weakness despite treatment

- Fever >101°F with back pain (possible infection)

- Nocturnal pain worse than daytime pain (possible tumor)

- Unexplained weight loss with back pain

- Significant trauma in elderly patients (fracture risk)

Call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room immediately

Need Treatment for Your Injuries?

Don't wait for your injuries to worsen. Get same-day evaluation and treatment from our accident injury specialists. We accept Letter of Protection—$0 out of pocket until your case settles.

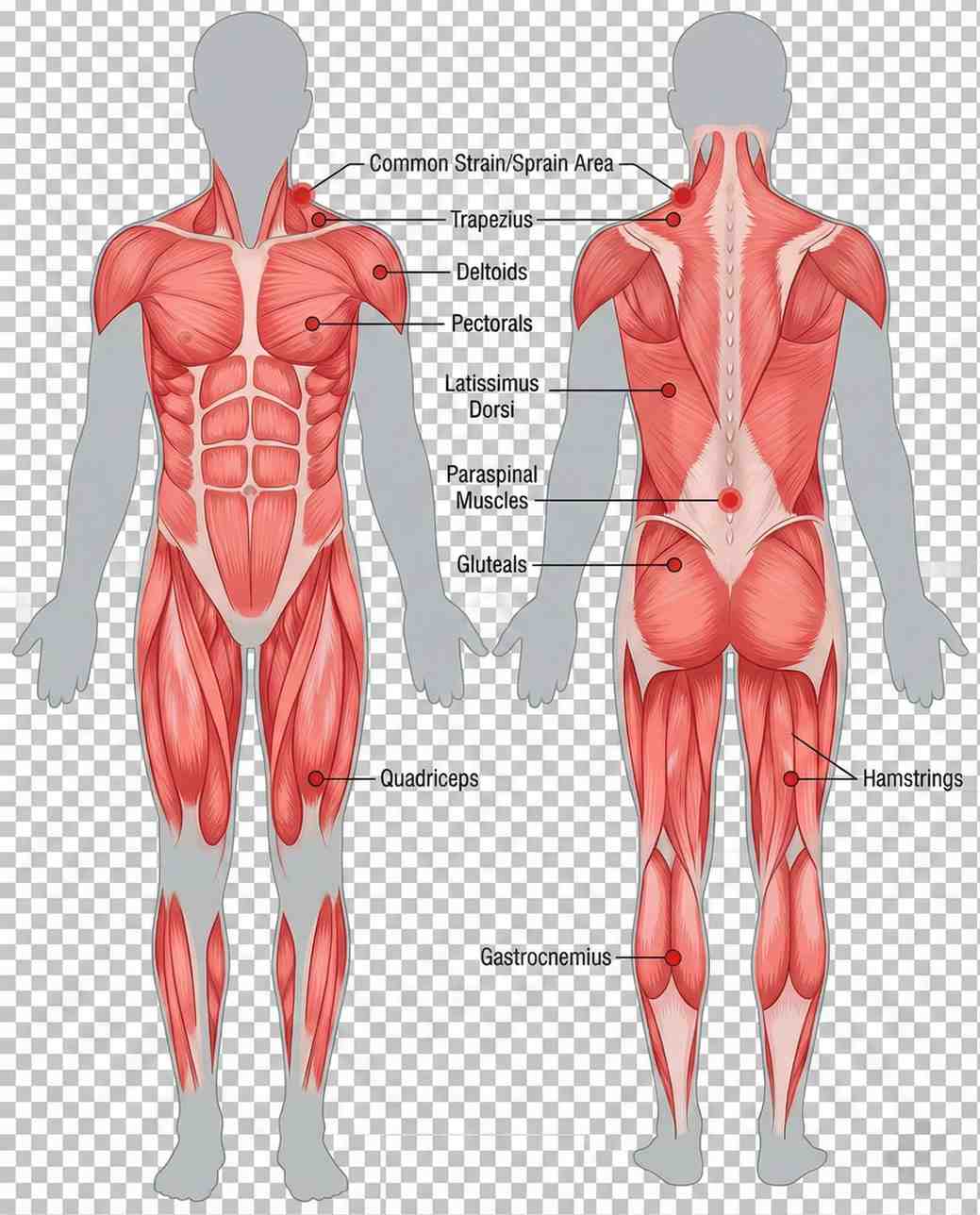

Soft Tissue Damage

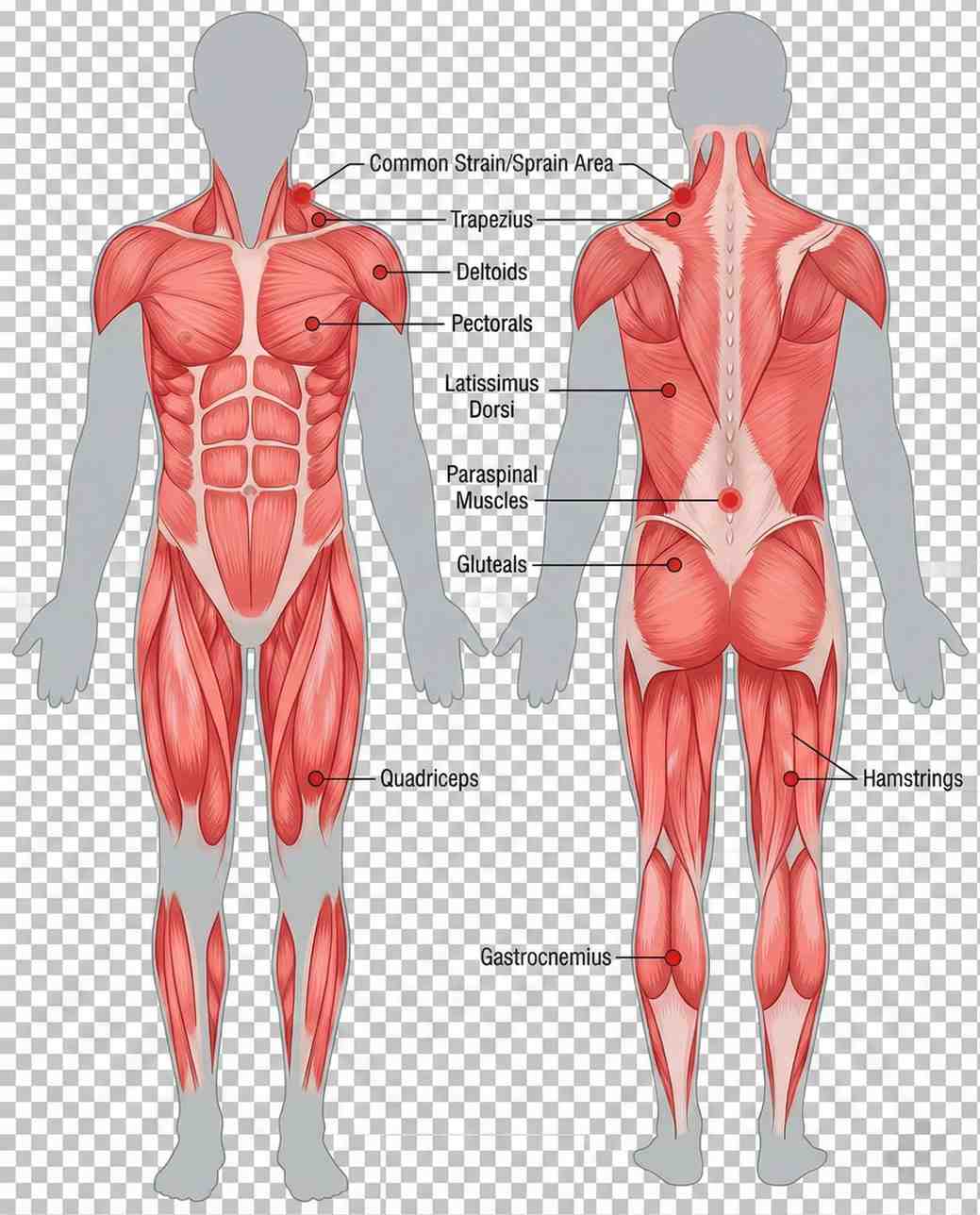

Soft tissue injuries encompassing muscles, tendons, and ligaments account for over 70% of all accident-related injuries. These injuries range from minor strains resolving in weeks to severe ruptures requiring surgical repair. Despite often lacking dramatic imaging findings, soft tissue injuries can cause substantial pain, functional impairment, and long-term disability. AccidentDoc Pasadena provides comprehensive evaluation and treatment of all soft tissue injury grades.

Soft tissues include all non-bony, non-neural structures: skeletal muscles that generate movement, tendons connecting muscles to bones, ligaments connecting bones to each other, and fascia providing structural support and force transmission. Understanding the grading system for soft tissue injuries guides treatment selection and prognosis.

Muscle injuries are classified by severity: Grade 1 (Mild Strain) involves microscopic muscle fiber tears with minimal loss of strength and function. Pain develops gradually and is typically manageable with over-the-counter medication. Swelling is minimal, and ecchymosis (bruising) is often absent. Patients maintain >80% of normal strength. Recovery typically occurs within 2-3 weeks with conservative care.

Grade 2 (Moderate Strain/Partial Tear) involves significant muscle fiber disruption with measurable loss of strength and function. A palpable defect or divot may be felt at the injury site. Pain is moderate to severe, especially with muscle activation. Swelling appears within 24-48 hours, and ecchymosis develops 2-5 days post-injury as blood dissects through tissue planes. Patients retain 50-80% of normal strength. Recovery requires 6-12 weeks including rehabilitation.

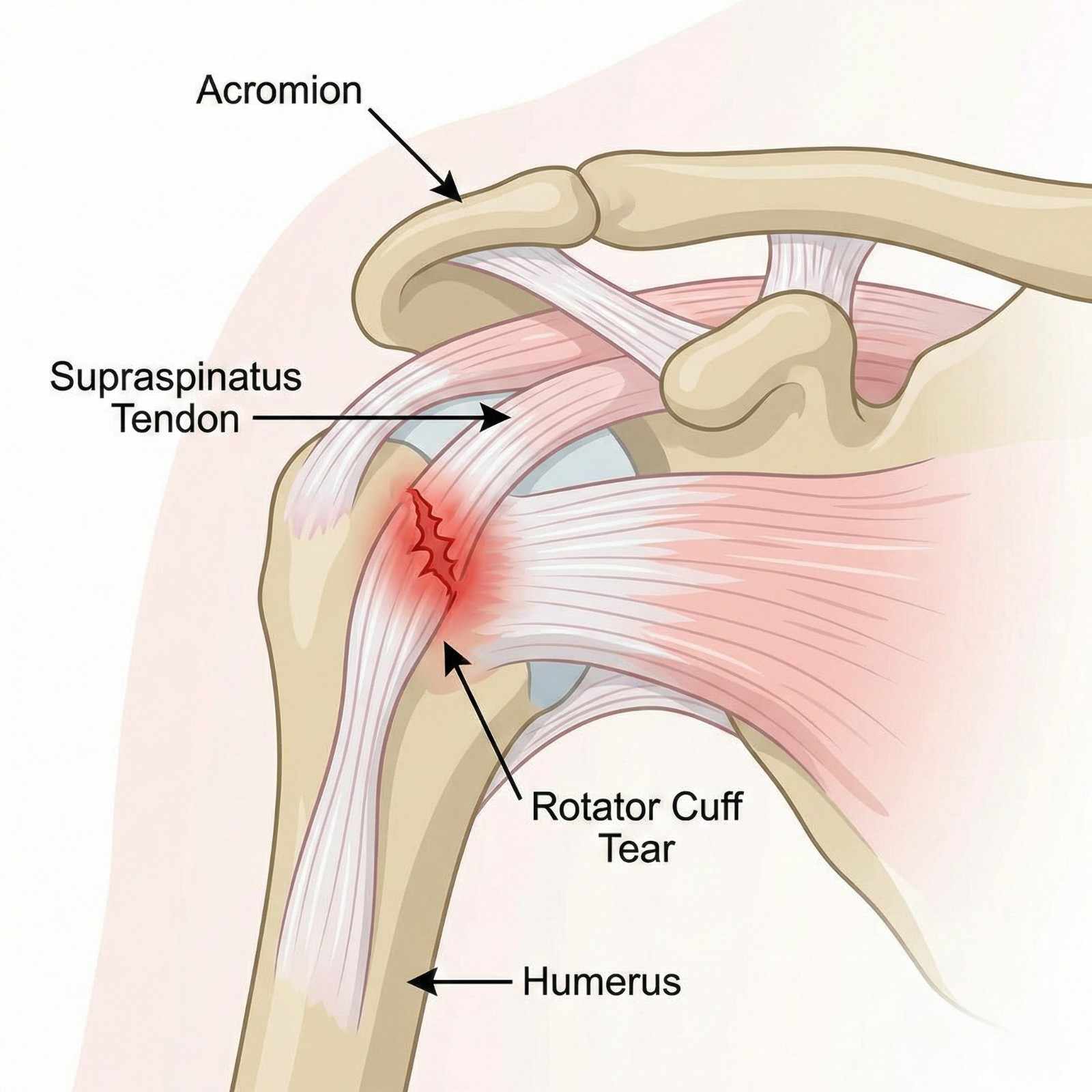

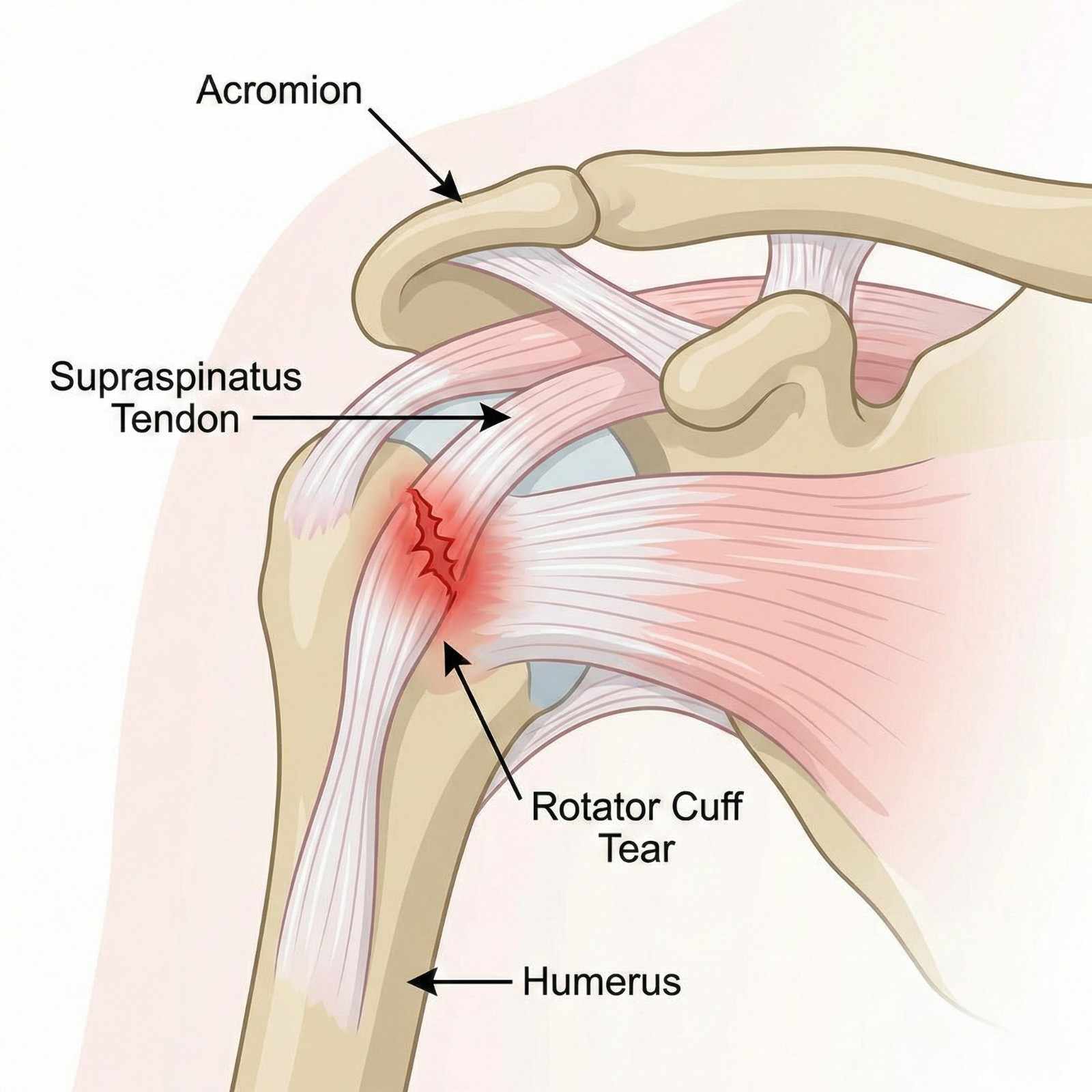

Grade 3 (Severe Strain/Complete Rupture) involves full-thickness muscle or musculotendinous junction tear with complete loss of function. A visible or palpable defect exists, often with bunching of the retracted muscle belly. Initial pain may be severe but can paradoxically decrease as torn nerve endings separate. Massive ecchymosis develops. Patients have <50% of normal strength or complete inability to contract the muscle. These injuries often require surgical repair, particularly in critical muscles like Achilles tendon, patellar tendon, or rotator cuff, with 3-6 month recovery.

Tendon injuries follow similar grading: Grade 1 (tendinopathy) involves inflammatory changes and microscopic fiber disruption without gross tear. Grade 2 (partial tear) involves significant fiber disruption with preserved continuity. Grade 3 (complete rupture) is full-thickness tear with loss of continuity, causing complete functional loss and requiring surgical repair in most locations.

Ligament sprains use the same three-grade classification: Grade 1 involves microscopic tears with preserved stability (stress testing shows normal joint stability). Grade 2 involves partial tear with mild-to-moderate laxity on stress testing but preserved endpoint. Grade 3 involves complete tear with marked laxity and absent endpoint, often requiring surgical reconstruction.

Contusions (bruises) result from direct trauma causing muscle crushing, capillary rupture, and hematoma formation without fiber tearing. They range from mild (minor pain, small hematoma) to severe (large intramuscular hematoma causing compartment-like pressure and possible myositis ossificans—heterotopic bone formation in muscle). Seatbelt contusions across the shoulder, chest, and abdomen are classic accident injuries, sometimes associated with underlying organ injury (liver or spleen in severe cases).

Soft tissue injuries result from multiple mechanisms in accident scenarios. Seatbelt trauma represents a unique injury pattern where the three-point restraint system loads soft tissues in a diagonal band across the chest, shoulder, and abdomen during sudden deceleration. The shoulder belt crosses the pectoralis major muscle, anterior deltoid, and trapezius, potentially causing strains or contusions. Chest wall contusions can extend to rib fractures or costochondral separation in severe impacts. Abdominal seatbelt injuries include rectus abdominis and oblique muscle strains, with severe cases causing bowel or mesenteric injury (seatbelt syndrome). The characteristic diagonal bruise pattern appearing 24-48 hours post-accident is pathognomonic for seatbelt loading.

Airbag deployment generates unique injuries through rapid inflation (deploying at 200+ mph). Upper extremity injuries occur when hands are positioned on the steering wheel in improper positions (10-and-2 versus recommended 9-and-3), with airbag impact causing wrist extension injuries, forearm contusions, and finger dislocations. Facial and chest contusions result from airbag contact, occasionally causing ocular injuries if eyeglasses shatter. Chemical burns from airbag propellant (sodium azide) can occur, presenting as erythematous rash on contact areas.

Dashboard and interior impacts cause location-specific injuries: knee impact against dashboard produces quadriceps contusions, patellar injuries, and posterior cruciate ligament tears (dashboard knee). Shoulder impact against door frames causes rotator cuff strains and contusions. Hip and thigh contusions occur from center console or door panel impacts. These injuries often present with massive ecchymosis developing over 3-5 days.

Slip-and-fall accidents generate injuries based on landing position and protective reflexes: landing on an outstretched hand (FOOSH injury) causes wrist and forearm soft tissue injuries plus possible fractures. Lateral falls produce hip, shoulder, and lateral thigh contusions. Catching oneself during a fall creates eccentric muscle loading (muscle lengthening under tension), particularly affecting quadriceps, hamstrings, and rotator cuff, leading to Grade 2 strains.

Workplace accidents including repetitive motion create overuse injuries: rotator cuff tendinopathy in overhead workers (painters, electricians, construction), lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) in tool users requiring repetitive wrist extension (carpentry, assembly work), and medial epicondylitis (golfer's elbow) in gripping activities. These cumulative trauma injuries are compensable under Texas workers' compensation when work activities are the major contributing cause.

Direct trauma from being struck by objects, equipment, or during falls creates contusions with potential complications including compartment syndrome (elevated pressure within fascial compartments compromising perfusion) requiring emergency fasciotomy, traumatic rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown releasing myoglobin causing acute kidney injury), and myositis ossificans (heterotopic bone formation in healing muscle hematoma).

- Seatbelt trauma - diagonal chest/shoulder contusions, abdominal strains

- Airbag deployment - upper extremity contusions, wrist extension injuries

- Dashboard/interior impacts - knee contusions, quadriceps strains, shoulder injuries

- Slip-and-fall - FOOSH injuries, hip contusions, eccentric muscle loading

- Workplace repetitive motion - rotator cuff tendinopathy, epicondylitis

- Direct trauma - struck by objects causing contusions and possible compartment syndrome

- Sports-type injuries during accidents - sudden acceleration/deceleration strains

Soft tissue injury symptoms follow a characteristic temporal pattern useful for diagnosis and patient education. Immediate symptoms (0-6 hours) include pain at the injury site, often described as sharp or aching, worsening with movement or palpation. Muscle spasm or cramping develops as protective splinting. Swelling is typically minimal immediately post-injury unless significant vascular disruption occurred. Range of motion is reduced due to pain and protective guarding. Strength is decreased if muscle fibers are torn, though initial adrenaline and pain-mediated guarding can mask true weakness.

Delayed symptoms (24-72 hours) often exceed initial symptoms as inflammatory cascade peaks. Swelling becomes apparent as capillary permeability increases and inflammatory mediators accumulate. Ecchymosis (bruising) appears, typically 2-5 days post-injury, as extravasated blood dissects through tissue planes and breaks down. Bruise color evolution follows a predictable pattern: red-purple initially (oxyhemoglobin), blue-purple days 1-3 (deoxyhemoglobin), green days 4-6 (biliverdin), yellow-brown days 7+ (bilirubin and hemosiderin). Stiffness peaks in morning or after prolonged static postures as inflammatory exudate accumulates during immobility.

Functional limitations depend on injury location and severity: shoulder injuries impair overhead reaching, dressing, and hair grooming. Elbow and forearm injuries affect lifting, carrying, and keyboard use. Hip and quadriceps injuries impair stair climbing, rising from chairs, and squatting. Hamstring injuries affect walking speed, running, and bending. Seemingly minor soft tissue injuries can cause substantial functional impairment and work disability, particularly in labor-intensive occupations.

Chronic symptoms develop when acute injuries aren't properly rehabilitated: persistent weakness from inadequate strengthening allows compensatory movement patterns stressing other structures. Adhesions and scar tissue formation in healing muscle limits flexibility and creates pain with stretching. Tendinopathy develops from inadequately healed tendon undergoing repetitive loading before tissue remodeling completes. Chronic pain syndromes including myofascial pain with trigger points can perpetuate pain months to years after initial injury.

Physical examination reveals specific findings: palpable muscle spasm or taut bands, point tenderness at the injury site, possible palpable defect or gap in Grade 2-3 injuries, ecchymosis with characteristic distribution, reduced active range of motion (patient-initiated movement) out of proportion to passive range of motion (examiner moves limb—less limited as muscle activation not required), pain with resisted testing of specific muscle groups, and strength deficit quantified using manual muscle testing graded 0-5 (0=no contraction, 1=flicker, 2=movement with gravity eliminated, 3=movement against gravity only, 4=movement against some resistance, 5=normal strength).

| Symptom | Timing / Description |

|---|---|

| Pain at injury site | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Muscle spasm/cramping | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Reduced range of motion | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Decreased strength | Immediate (0-6 hours) |

| Swelling | Delayed (24-48 hours) |

| Ecchymosis (bruising) | Delayed (2-5 days) |

| Morning stiffness | Delayed (24-72 hours) |

| Functional limitations | Immediate to Chronic |

| Persistent weakness | Chronic (>6 weeks) |

| Trigger points | Chronic (>3 months) |

Soft tissue injury diagnosis relies heavily on clinical examination, with imaging serving a confirmatory role or ruling out associated bony injuries. Our systematic approach ensures accurate diagnosis and guides treatment selection.

Clinical examination begins with inspection noting ecchymosis distribution (diagonal across chest suggests seatbelt, localized suggests direct impact), swelling patterns, and visible deformities. Palpation identifies point tenderness, muscle spasm or taut bands, palpable defects or gaps suggesting complete tears, and temperature changes (warmth suggests active inflammation). Active and passive range of motion testing differentiates muscular limitation (active more limited than passive) from joint capsule restriction (both equally limited). Resisted strength testing isolates specific muscle groups: manual resistance applied while patient contracts muscle reproduces pain in injured muscle/tendon and reveals strength deficits graded 0-5.

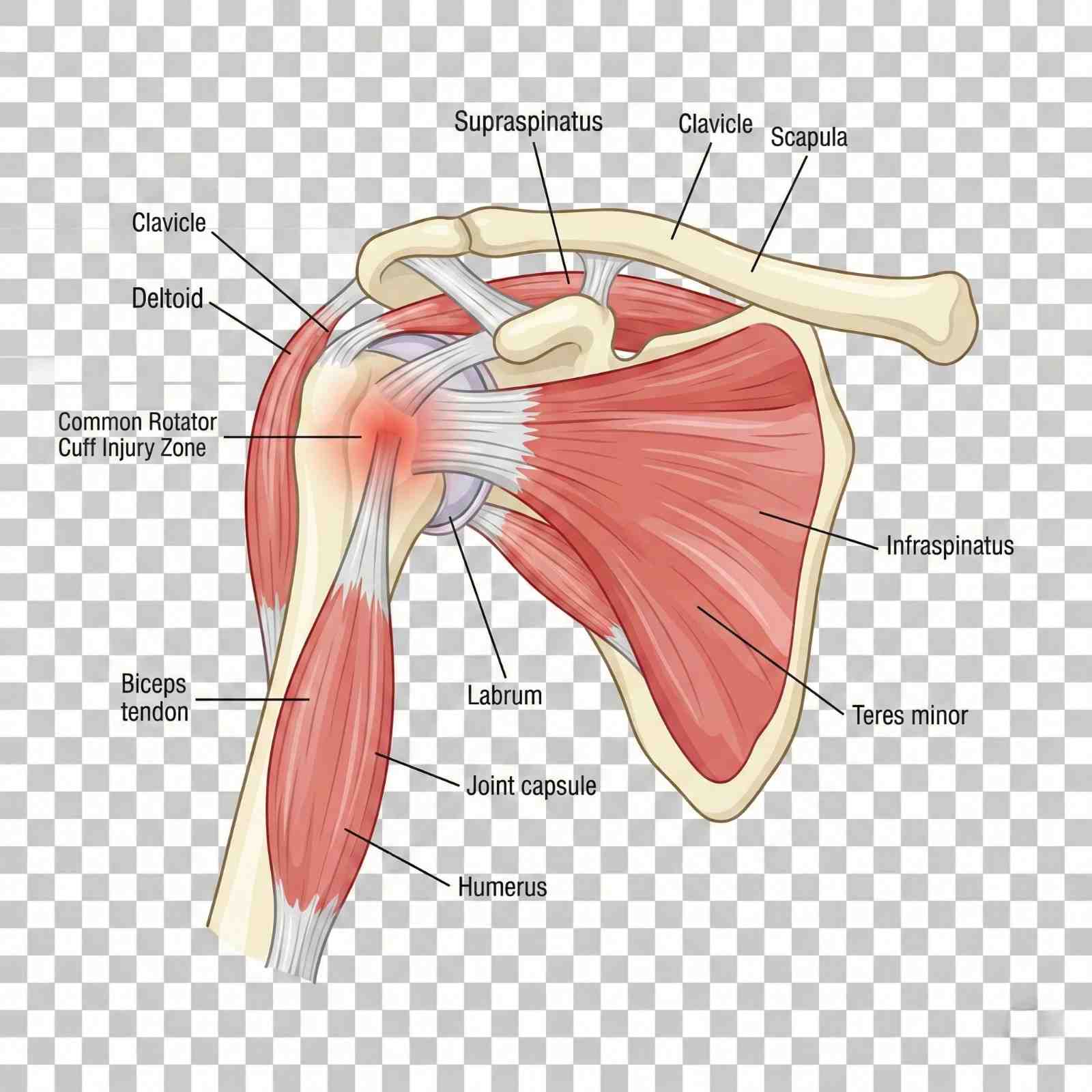

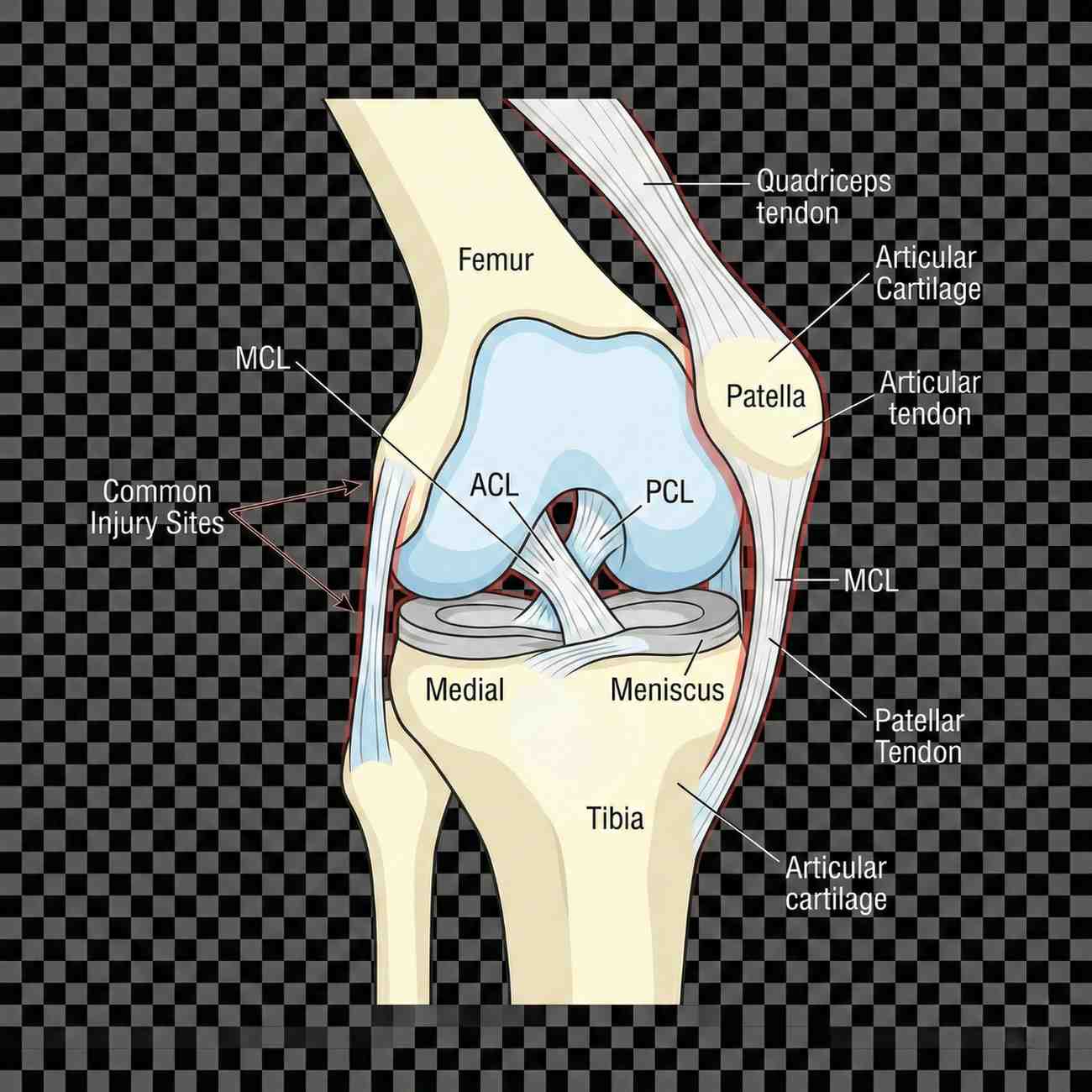

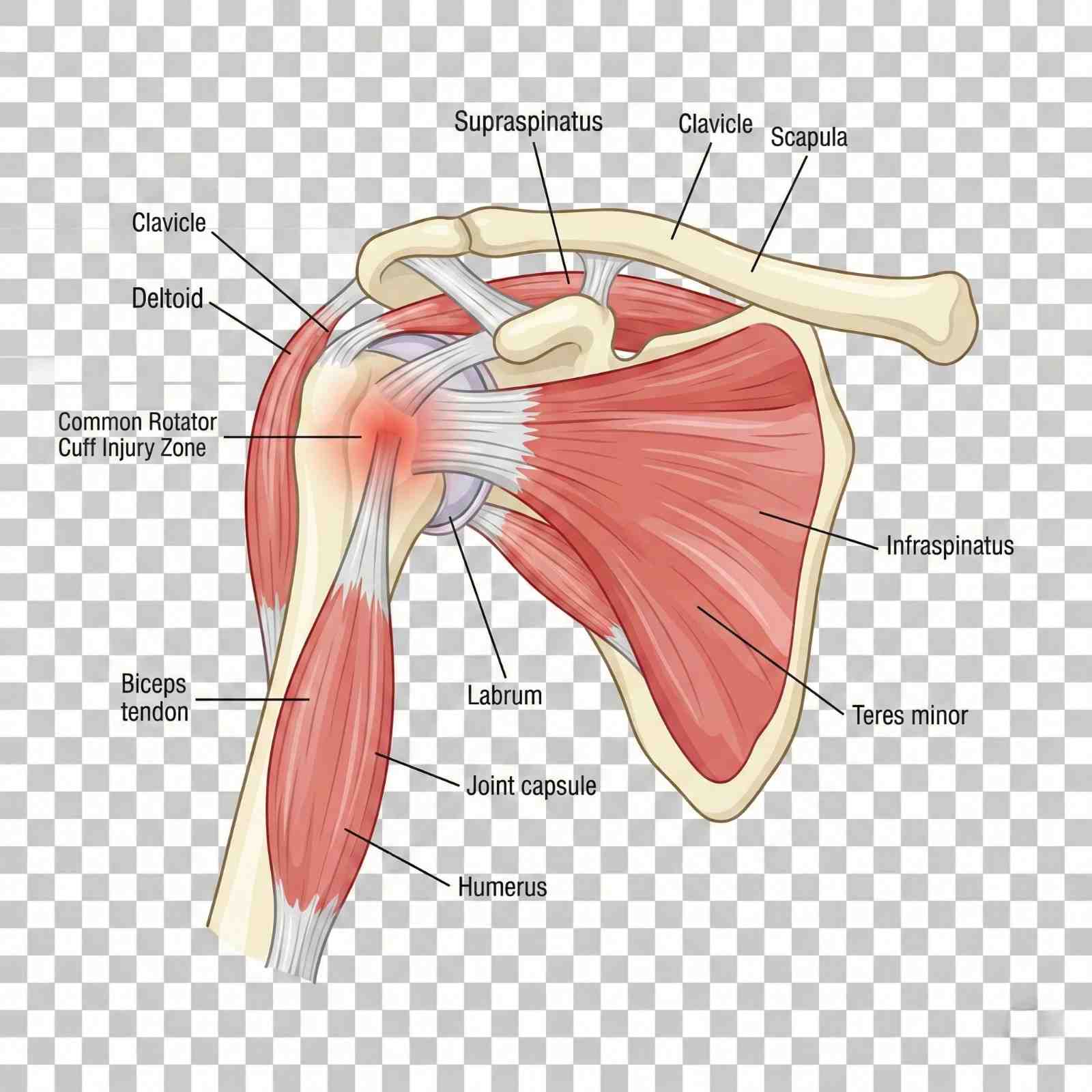

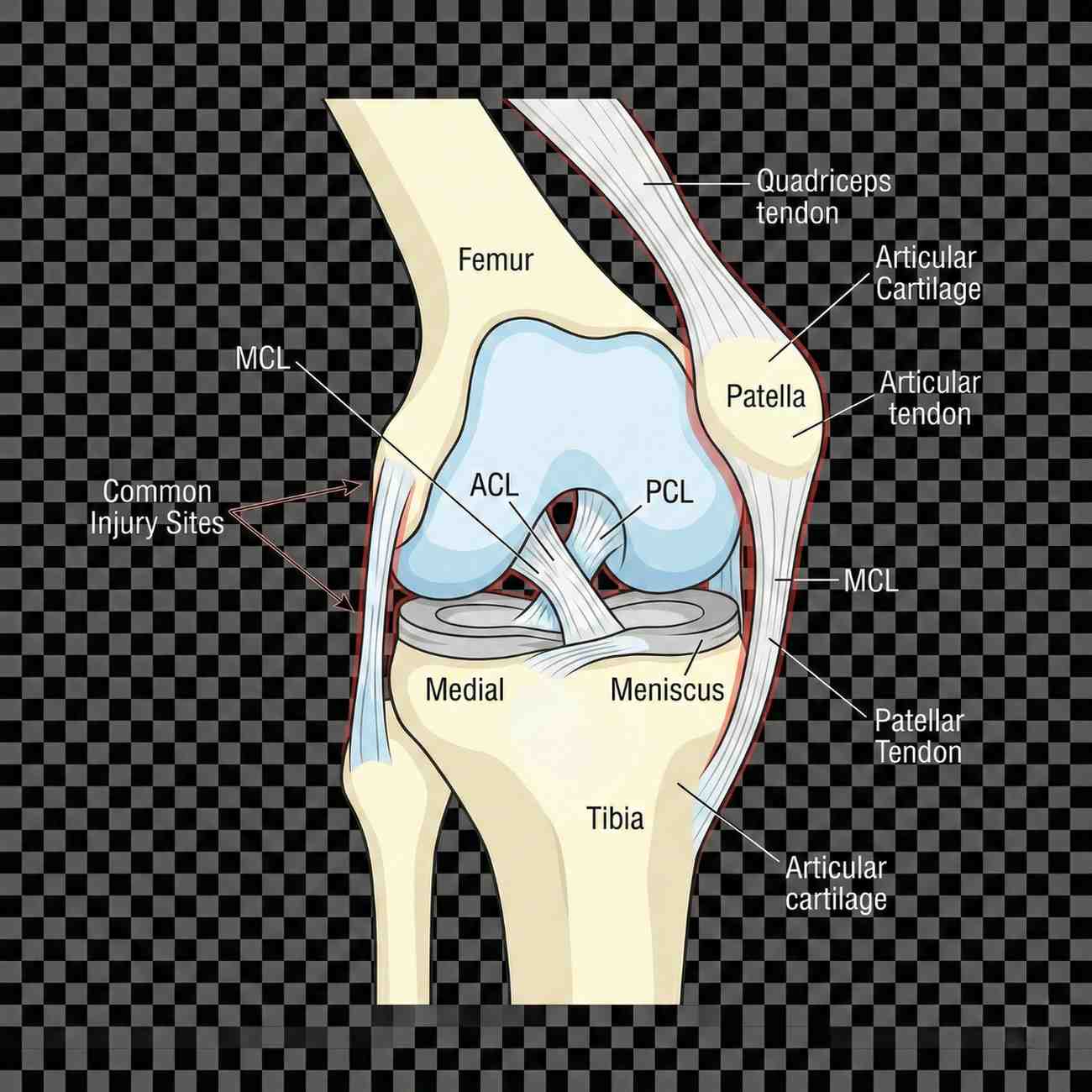

Special tests target specific structures: for shoulder injuries, we perform empty can test (supraspinatus), drop arm test (supraspinatus tear), Hawkins-Kennedy test (impingement), and Speed's test (biceps tendon). For knee, we assess Lachman and anterior drawer (ACL), posterior drawer (PCL), varus and valgus stress (collateral ligaments), and McMurray's test (meniscus). For ankle, anterior drawer and talar tilt assess ligament integrity. Positive tests combined with mechanism and clinical presentation establish diagnosis.

Imaging selection follows clinical indication: Plain X-rays are initial imaging for any injury involving joint or bone proximity, ruling out fractures, dislocations, and foreign bodies. X-rays don't visualize soft tissue injuries directly but show secondary signs like joint effusion or soft tissue swelling. Ottawa rules guide ankle and knee X-ray necessity, reducing unnecessary imaging.

Ultrasound is excellent for superficial soft tissue evaluation including rotator cuff tears, Achilles tendon ruptures, patellar tendon tears, muscle tears with hematoma, and joint effusions. Ultrasound is real-time, allows dynamic assessment (imaging during movement), and is cost-effective. Limitations include operator dependence and limited depth penetration (not useful for deep structures like hip rotator cuff).

MRI provides definitive soft tissue imaging with superior contrast resolution, visualizing muscle tears, tendon tears (complete vs partial), ligament injuries, cartilage damage, bone marrow edema, and joint effusions. MRI is ordered when clinical examination suggests Grade 2 or 3 injury, surgical intervention is considered, or diagnosis remains unclear after examination and X-ray. For medico-legal cases, MRI provides objective documentation of injury severity.

CT scanning is reserved for complex fractures or when MRI is contraindicated (pacemaker, certain metal implants). CT arthrography (CT after intra-articular contrast injection) can evaluate cartilage and ligaments when MRI unavailable. Electrodiagnostic studies (EMG/NCS) are rarely needed for pure soft tissue injuries but can identify associated nerve injuries (brachial plexus injury with shoulder trauma, radial nerve injury with humeral fracture, peroneal nerve injury with knee dislocation).

Soft tissue injury treatment progresses through phases targeting inflammation reduction, pain control, tissue healing, and functional restoration. Our evidence-based protocols optimize recovery while preventing chronic dysfunction.